Review: One Night Only

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness | Mami Sunada | Japan | 2013 | 126 min

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Friday, January 23 at 7:00pm»

While not particularly inspired documentary filmmaking, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness provides plenty of behind-the-scenes moments to keep Studio Ghibli fans content until the return of The Wind Rises and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya on campus.

Studio Ghibli fans like myself had a year of mixed emotions in 2014. On the one hand, we had two terrific Ghibli features to enjoy: Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, both of which made my list of favorite films of last year. On the other hand, we know that these are probably the last feature films by two great masters of animation, and the future of Studio Ghibli itself is uncertain. Luckily, campus filmgoers will be able to revisit both Ghibli features early in 2015: A subtitled DCP of The Wind Rises will screen at the UW Cinematheque on Saturday, January 24 at 2:00pm; and Princess Kaguya will return at the Union South Marquee Theater the weekend of Feburary 28.

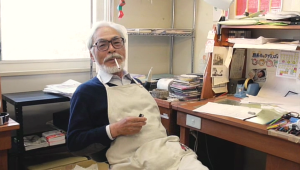

The UW Cinematheque will also provide a behind-the-scenes look at Studio Ghibli during the production of both of these films with Mami Sunada’s documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness on Friday, January 23 at 7:00pm. The documentary is not a particularly good introduction to the Studio Ghibli universe, nor does it have much to say about the films themselves (in fact we see very little from the films until a montage of clips near the end). But for fans of Studio Ghibli there’s quite a bit here to enjoy despite some uninspired documentary filmmaking. We spend most of the film with Miyazaki himself, and his warm contemplative presence, juxtaposed with his cold perfectionism and competitiveness, makes for a intriguing if occasionally underwhelming portrait of one of the world’s great filmmakers.

Not all of the keys to the Kingdom

It is important to first note what the film is not. It is not about Miyazaki beyond what he agrees to offer the filmmakers while at work and occasionally at home (or his personal atelier near the studio). More importantly, despite the film’s promotional materials, it is not really about the working relationship between Miyazaki and Takahata. The lack of direct participation from Takahata in the documentary is particularly disappointing. Takahata is discussed and his importance in Studio Ghibli history is explained, but he becomes a structuring absence in the film. We see some of the consequences of the tension between Miyazaki and Takahata, but we barely see them interact (and then only at the end).

The lack of Takahata’s participation is somewhat compensated by the abundant access to Toshio Suzuki, who as producer for both Miyazaki and Takahata over the years has had a significant influence on Studio Ghibli despite not being an animator himself. Suzuki is the ultimate facilitator and problem solver, and he seems to spend most of his time simply trying to make things happen. His resigned acceptance of the working methods of both filmmakers is a testament to his commitment to quality. He always seems to have a smile on his face, despite the fact that everyday he deals with with deadlines and their financial consequences. Suzuki’s work on the ground allows the work of Miayzaki and Takahata to soar.

A recurring theme is how animation is a labor of love, because the process is so difficult that you better love what you’re doing to devote so much of your life to it. Despite their profound admiration for Miyazaki, many Studio Ghibli employees find it challenging and often difficult to work with him. Miyazaki himself makes clear in archival footage of a new employee orientation meeting that if any staff member does not find what they’re doing fulfilling, they should quit. Perhaps the most surprising example of this comes from a project pitch meeting with Miyazaki’s son, Gorō, who has directed two Ghibli features, Tales from Earthsea (2006) and From up on Poppy Hill (2011). Gorō admits that he’s not sure if animation is really his true calling, and he’s reluctant to take on another project that has been proposed for him in the meeting just for the sake of doing another feature. Even Miyazaki himself, in some of his more introspective moments, wonders aloud if his work has any true lasting value. Structurally speaking, the climax of the documentary is not just the completion of The Wind Rises but Miyazaki’s retirement press conference, which gives the film a somewhat melancholy tone.

Nerd Alert

Many details that will appeal to animation fans and otaku (devoted anime fans), including Miyazaki’s obvious contempt for otaku. A brief shot of a “cosplay Miyazaki” is so convincing that I was momentarily surprised that Miyazaki was not getting mobbed in the middle of a convention. The process behind casting respected anime director Hideaki Anno (Neon Genesis Evangelion) as the lead voice actor in The Wind Rises is both amusing and intriguing. After complaining about the quality of the voice actors auditioning for the role, Miyazaki slowly realizes that the voice he’s looking for is like Anno’s when someone jokingly mentions Anno’s name. A quick look at an online video clip of an interview with Anno confirms Miyazaki’s memory and curiosity, which leads to a series of phone calls and auditions. Anno was the key animator on the “God Warrior” in Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) before moving on to his own work, so the reunion of sorts is kind of a nerd alert moment in the film. Of course, having only seen the Disney dubbed version of The Wind Rises in the theater, I was completely unaware of Anno’s participation in the film. This provides one more reason to re-visit The Wind Rises in its Japanese language / English subtitled version at the UW-Cinematheque.

Do all of the details in The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness add up to a good documentary? Not really. It rarely goes beyond standard DVD bonus feature ambition or quality. Despite my personal interest in the subject matter, not all of the sequences are equally engaging or informative, and the soundtrack occasionally lapses into some pretty bland musical accompaniment. The film is nowhere near the quality of other recent documentaries at the UW Cinematheque, like Stray Dog, and as a so-so doc it is an odd choice to kick off the Spring series Friday night. But since the rest of their opening weekend includes The Wind Rises and Citizen Kane, it is pretty safe to say that the Cinematheque comes out ahead, as usual. For Ghibli fans Kingdom is more or less critic proof because it documents such a pivotal time in its history—perhaps the end of the studio as a producer of new features. Anyone interested in that history should catch it.