Welles Week: Part Three of Five

Welles Week: Part Three of Five

Mr. Arkadin—The Comprehensive Version | Orson Welles | 1955, new edit 2006 | Spain, France | 106 min

Confidential Report will screen at the UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, on Saturday, Feburary 21 at 7:00pm»

Jay Antani from CinemaWriter.com looks at the “cinema equivalent of a down-and-out scamp with an irresistible personality,” Mr. Arkadin (1955), and concludes that it is less a movie than a dream of a movie you thought you once watched, an ethereal experience conjured by the most wizardly of filmmakers.

Today’s Welles Week entry comes from our friend Jay Antani at CinemaWriter.com. Back in 2012, Jay looked at the Criterion Collection DVD release of The Complete Mr. Arkadin, and his review of what Criterion called the “Comprehensive Version” of Mr. Arkadin appears below. For more about the history of Mr. Arkadin, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s “The Seven Arkadins,” and J. Hoberman’s “Welles Amazed: The Lives of Mr. Arkadin.”

Please note that this review is for the 106-minute “Comprehensive Version” of Mr. Arkadin. For the Orson Welles: A Centennial Celebration series, the UW Cinematheque will screen a 98-minute 35mm print of Confidential Report, one of several versions of the film.

An exasperating movie whose beauties need to be extracted from the mire of its bungling weaknesses. Mr. Arkadin is the cinema equivalent of a down-and-out scamp with an irresistible personality, a movie whose topsy-turvy production history is typically Wellesian. Shot in 1954 as a Spanish-French co-production, Welles fiddled with editing Arkadin for months before his producer wrested it away and edited it as a conventional, chronologically linear story (contrary to Welles’s more intricate, Citizen Kane-like vision of it) and called it Confidential Report. That was one of several release versions of Mr. Arkadin until the Criterion Collection helped assemble what it calls The Comprehensive Version, that is, a version of the film as close to Welles’s vision as possible. The Comprehensive Version stays true to the flashback structure that Welles had in mind and posits about 15 additional minutes of footage in conformance with his original script. So, if you’re going to watch Mr. Arkadin, Criterion’s Comprehensive Version is probably the one best in line with what Welles would want you to see.

An exasperating movie whose beauties need to be extracted from the mire of its bungling weaknesses. Mr. Arkadin is the cinema equivalent of a down-and-out scamp with an irresistible personality, a movie whose topsy-turvy production history is typically Wellesian. Shot in 1954 as a Spanish-French co-production, Welles fiddled with editing Arkadin for months before his producer wrested it away and edited it as a conventional, chronologically linear story (contrary to Welles’s more intricate, Citizen Kane-like vision of it) and called it Confidential Report. That was one of several release versions of Mr. Arkadin until the Criterion Collection helped assemble what it calls The Comprehensive Version, that is, a version of the film as close to Welles’s vision as possible. The Comprehensive Version stays true to the flashback structure that Welles had in mind and posits about 15 additional minutes of footage in conformance with his original script. So, if you’re going to watch Mr. Arkadin, Criterion’s Comprehensive Version is probably the one best in line with what Welles would want you to see.

Welles himself dons the beard and opera cape of the titular Arkadin, an eccentric, pompous, egotistical billionaire (a variation on the kind of roles that Welles excelled at playing, beginning with the equally tragic, equally imposing Charles Foster Kane). Claiming amnesia, Arkadin enlists the services of Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden), an American ex-pat in post-War Europe, a black-market smuggler, to investigate his origins. Van Stratten’s job is to find out how Arkadin came to become Arkadin; that is, how a poor refugee from Poland rose from the ranks to become one of the world’s most legendary industrialists. It’s only as Van Stratten becomes aware of the trail of bodies lying in the wake of his investigation that he suspects that Arkadin has more up his ample sleeves than he bargained for, and that he himself is in line to be one of Arkadin’s victims or his fall guy. What links Van Stratten to Arkadin is the latter’s daughter, Raina (Paola Mori). Van Stratten is in love with Raina while Arkadin wants to shield his daughter from anyone with knowledge of his less-than-squeaky-clean past.

Welles himself dons the beard and opera cape of the titular Arkadin, an eccentric, pompous, egotistical billionaire (a variation on the kind of roles that Welles excelled at playing, beginning with the equally tragic, equally imposing Charles Foster Kane). Claiming amnesia, Arkadin enlists the services of Guy Van Stratten (Robert Arden), an American ex-pat in post-War Europe, a black-market smuggler, to investigate his origins. Van Stratten’s job is to find out how Arkadin came to become Arkadin; that is, how a poor refugee from Poland rose from the ranks to become one of the world’s most legendary industrialists. It’s only as Van Stratten becomes aware of the trail of bodies lying in the wake of his investigation that he suspects that Arkadin has more up his ample sleeves than he bargained for, and that he himself is in line to be one of Arkadin’s victims or his fall guy. What links Van Stratten to Arkadin is the latter’s daughter, Raina (Paola Mori). Van Stratten is in love with Raina while Arkadin wants to shield his daughter from anyone with knowledge of his less-than-squeaky-clean past.

With its hectic, lurching pace, uneven (if not downright awful) performances and a hodgepodge of a script riddled with scenes that barely make dramatic sense, Mr. Arkadin wears all the battle scars of a movie hobbled by budget and a slapdash production (and post-production) made all the more tenuous by Welles’s capricious working methods. That his vision for Arkadin was never fully realized is less a surprise than Criterion being able to piece together the Comprehensive Version, thanks to meticulous scholarship and research.

As pulp noir, Mr. Arkadin is not particularly successful because it’s haphazard elements prevent any coherent sense of story and suspense. Van Stratten, as a character, is never very appealing; he never projects the authentic desperation and contained poise of a noir anti-hero, a fugitive in search of redemption, and there’s nothing romantic about his persona at all. What Welles needed was a strong, silent Robert Mitchum or Sterling Hayden type. What he got was someone closer to William Bendix by way of Andy Devine, garrulous and irritable.

As pulp noir, Mr. Arkadin is not particularly successful because it’s haphazard elements prevent any coherent sense of story and suspense. Van Stratten, as a character, is never very appealing; he never projects the authentic desperation and contained poise of a noir anti-hero, a fugitive in search of redemption, and there’s nothing romantic about his persona at all. What Welles needed was a strong, silent Robert Mitchum or Sterling Hayden type. What he got was someone closer to William Bendix by way of Andy Devine, garrulous and irritable.

Granted, Arden’s performance speaks less of his talent and more of Welles’s ill-thought-out direction of it. Indeed, weak or slapdash performances abound in Arkadin: Mori as Van Stratten’s love interest is neither particularly sexy nor charming, and she comes off as just a rich girl wearing the costume of a grown-up sophisticate; Patricia Medina as Mily, who also wants the goods on Arkadin, is so temperamentally all over the place, we can’t be sure if she’s a sly gold-digger or an innocent naif in a bad situation. In any case, Welles’s preoccupation seems to have been with his own role. Welles plays Arkadin with his always-amusing blend of kitschy, charismatic bravado; he’s a commanding presence eliciting either delighted chuckles from fans of his larger-than-life stagecraft or groans from those who’ve had enough.

Still, for all its flaws, Mr. Arkadin is a mesmerizing experience, a schizoid crime caper that’s half-potboiler and half-reverie. While the script threatens to implode with its incoherence and the acting can be awful and the pacing erratic, there are also scenes of pure cinematic bliss. And the last is why we come to Welles anyway. The scenes, for example, in Arkadin’s Spanish castle draw from Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible in their expressive, geometric use of interiors and of the vast landscapes. The sequences in Munich, Mexico, North Africa and a terrifically oddball one inside Arkadin’s storm-tossed ship are all hallmarks of kooky expressionism (a la Carol Reed’s The Third Man) melded with a chic, ultra-modern visual posturing that presages Fellini and Antonioni.

Still, for all its flaws, Mr. Arkadin is a mesmerizing experience, a schizoid crime caper that’s half-potboiler and half-reverie. While the script threatens to implode with its incoherence and the acting can be awful and the pacing erratic, there are also scenes of pure cinematic bliss. And the last is why we come to Welles anyway. The scenes, for example, in Arkadin’s Spanish castle draw from Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible in their expressive, geometric use of interiors and of the vast landscapes. The sequences in Munich, Mexico, North Africa and a terrifically oddball one inside Arkadin’s storm-tossed ship are all hallmarks of kooky expressionism (a la Carol Reed’s The Third Man) melded with a chic, ultra-modern visual posturing that presages Fellini and Antonioni.

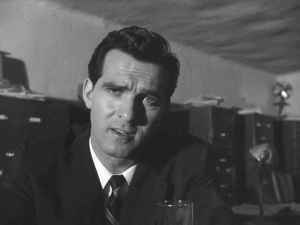

A personal favorite is the scene in which Arkadin asks Van Stratten to investigate his past. The exchange takes place in what is presumably a secretary’s office, littered with filing cabinets, but, in the spell of the movie’s imagery and setting, this office becomes an obscure catacomb in some bizarre alternate reality. Watching this scene, I always wonder what secrets those filing cabinets contain, why there are no windows in this “office,” and ponder the room’s stuffy, claustrophobic atmosphere. Knowing that Welles shot the movie in scattershot fashion, the scene and space have a hit-and-run, spit-and-glue quality about them. It’s a scene in which we really have to play “pretend,” because Welles insists we do and the fact that we don’t fully buy what’s being sold on-screen only pulls us more insistently into the story.

A personal favorite is the scene in which Arkadin asks Van Stratten to investigate his past. The exchange takes place in what is presumably a secretary’s office, littered with filing cabinets, but, in the spell of the movie’s imagery and setting, this office becomes an obscure catacomb in some bizarre alternate reality. Watching this scene, I always wonder what secrets those filing cabinets contain, why there are no windows in this “office,” and ponder the room’s stuffy, claustrophobic atmosphere. Knowing that Welles shot the movie in scattershot fashion, the scene and space have a hit-and-run, spit-and-glue quality about them. It’s a scene in which we really have to play “pretend,” because Welles insists we do and the fact that we don’t fully buy what’s being sold on-screen only pulls us more insistently into the story.

I suppose that these details—some deliberate, some incidental, some subjective—are what sets Mr. Arkadin apart. Details packed into moments that combine to make Arkadin less a movie than a dream of a movie you thought you once watched. It’s that dream-like quality that makes this an eternal, ethereal experience, something that’s rarely felt at the movies. And only when the movies in question are conjured by the most wizardly of filmmakers.

Grade: B+

Directed by: Orson Welles

Written by: Orson Welles

Cast: Robert Arden, Orson Welles, Michael Redgrave, Patricia Medina, Akim Tamiroff, Paola Mori, Katina Paxinou, Gregoire Aslan, Peter van Eyck