Review: One Night Only

Review: One Night Only

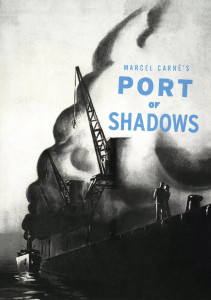

Port of Shadows (Le Quai des brumes) | Marcel Carné | France | 1938 | 90 min

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Wednesday, July 1, 7pm»

About 28 minutes into Port of Shadows, there is a series of three shots whose beauty—both stylistically and within the context of the story—are almost unrivaled in the rest of this masterful film. In the midst of an extended scene within the contained space of a small bar, two of the characters are finishing a conversation outside. The camera then pans right and tracks in close to a window, out of which the two main characters, Jean (Jean Gabin) and Nelly (Michèle Morgan), stare into the distance. They have just met, and yet they have made an instant and unmistakable connection. The film then cuts to the object of their gaze—a gorgeous sunrise, promising hope and freedom beyond the dank confines of the bar where they are both hiding out. The film then cuts back to Jean and Nelly. Nelly turns away from the window to face Jean (and the camera) and reflects on that promise of light as a respite from the darkness in the world, and an all too brief one at that.

I love this short series of shots for two reasons: 1) they create an exceedingly perfect and simple encapsulation of the rest of the story, and 2) the camera, as it does whenever it pans or tracks, doesn’t just move—it glides.

Port of Shadows begins with Jean hitching a ride to the port town of Le Havre. He is a former soldier, having deserted the army to seek refuge from the fog of war. In doing so, he finds desire, jealousy, crime and passion. The film is one of the most masterful examples of the poetic realist movement in French cinema of the 1930’s, which is due in large part to the collaboration of Gabin, director Marcel Carné, and screenwriter Jacques Prévert.

Gabin remains one of my favorite actors. The world weariness that he effortlessly conveys is always compelling to me in any of his films, but it is especially so here. While he shows some of his characteristic temper that one sees in his other work, Gabin gives us a slow transformation from a man who is almost lumbering through town at the beginning of the film, to a man who is so much more vital. That vitality comes through, of course, in his scenes with the luminescent Michèle Morgan. Upon revisiting the film, it occurs to me that this may be one of my favorite screen pairings of all time. Morgan’s performance is every bit as striking as her eyes, which seem to have a color all their own, even in black and white. From bit role to major player, all of the other performances are outstanding as well, particularly Pierre Brasseur’s petulant heavy, Lucien, and Michel Simon’s nostalgia-starved Zabel.

Gabin remains one of my favorite actors. The world weariness that he effortlessly conveys is always compelling to me in any of his films, but it is especially so here. While he shows some of his characteristic temper that one sees in his other work, Gabin gives us a slow transformation from a man who is almost lumbering through town at the beginning of the film, to a man who is so much more vital. That vitality comes through, of course, in his scenes with the luminescent Michèle Morgan. Upon revisiting the film, it occurs to me that this may be one of my favorite screen pairings of all time. Morgan’s performance is every bit as striking as her eyes, which seem to have a color all their own, even in black and white. From bit role to major player, all of the other performances are outstanding as well, particularly Pierre Brasseur’s petulant heavy, Lucien, and Michel Simon’s nostalgia-starved Zabel.

A soldier, an artist, a drunken drifter, and a barman discussing society and existential crises—it might be the beginning of a quick joke in a lesser author’s hands, but in the hands of poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert, it is truly poetry put to screen. There is a touch of wry humor peppered across the film, but those moments are invariably punctuated by fatalistic reflection. Most of the lines in the script have the weight of aphorism, but it’s a soulful weight that never tips the scale of pretension. “Dream on your feet and you’ll fall down,” Jean says at one point, and it’s a line illustrative of the combination of dreamy, romantic notions and grounded, eloquent truths that this film puts forward. Prévert was one of the major screenwriters of this period, and he collaborated with Carné on multiple films. Revisiting Port of Shadows, I found myself surprised at how tight and well-constructed the script is, particularly the deft ways in which the characters intersect throughout the picture. Any intrigue exists to illuminate the characters, instead of the characters serving the machinations of the intrigue.

A soldier, an artist, a drunken drifter, and a barman discussing society and existential crises—it might be the beginning of a quick joke in a lesser author’s hands, but in the hands of poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert, it is truly poetry put to screen. There is a touch of wry humor peppered across the film, but those moments are invariably punctuated by fatalistic reflection. Most of the lines in the script have the weight of aphorism, but it’s a soulful weight that never tips the scale of pretension. “Dream on your feet and you’ll fall down,” Jean says at one point, and it’s a line illustrative of the combination of dreamy, romantic notions and grounded, eloquent truths that this film puts forward. Prévert was one of the major screenwriters of this period, and he collaborated with Carné on multiple films. Revisiting Port of Shadows, I found myself surprised at how tight and well-constructed the script is, particularly the deft ways in which the characters intersect throughout the picture. Any intrigue exists to illuminate the characters, instead of the characters serving the machinations of the intrigue.

Finally, there is Carné, whose name—like Prévert’s—is synonymous with poetic realism. As I mentioned earlier, Carné’s (and cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan’s) camera seems to glide whenever it is in motion. When it is still, it is not immobile so much as it is at peace, contemplative. And just as Gabin’s performance grows in vitality as the picture progresses, so does Carné mirror that vitality stylistically, through quicker pans (yet still measured) and crisper editing as the film nears its climax. Returning to the series of shots I mentioned at the beginning of this post, much the rest of that sequence is within the confines of a small, shady watering hole. And while some of the dialogue—excellent though it is—may seem like it’s taken from a one-act play, Carné delivers a resolutely cinematic vision throughout this sequence and the rest of the film as well.

Port of Shadows is a film about the brief happiness we are sometimes afforded, if we’re lucky. At 90 minutes, this film is a brief happiness that all Madison film lovers should afford themselves, whether or not you have seen it before (but especially if you haven’t). However dark the film itself may be, it is a bright light in the Madison summer moviegoing schedule, and thanks to the good folks at the UW Cinematheque, it will be a breathtaking big screen experience.