Review: One Night Only

Review: One Night Only

Chronopolis | Piotr Kamler | France | 1982 | 65 minutes

Rooftop Cinema, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Friday, June 3, 9:30pm»

James Kreul discusses Piotr Kamler’s Chronopolis, screening at MMoCA’s Rooftop Cinema series. He suggests that audiences should appreciate the film’s abstract qualities instead of insisting on narrative momentum.

Discussing Polish filmmaker Piotr Kamler’s Chronopolis (1982) presents a few obstacles for your humble reviewer. I will attempt to overcome these obstacles, because you should know about the film and see it if you can. It is not widely available through official sources, but it remains a unique vision that probably will appeal more to experimental animation aficionados than to conventional science fiction fans.

There are two versions of the film: a 65-minute cut which has voice over narration by French actor Michael (Hugo Drax in Moonraker) Lonsdale, and a 52-minute cut without narration and other changes. The program notes for Friday’s Rooftop Cinema screening suggest that they are showing the former, but I only had access to the later from personal resources. So as you read this, keep in mind that there could be some details that are more clearly explained (or differently described) in the version likely to be screened Friday night.

There are two principal sets of characters in Chronopolis, and without the Lonsdale narration to guide me I’ll draw on some frequently used ways to describe them.

There are two principal sets of characters in Chronopolis, and without the Lonsdale narration to guide me I’ll draw on some frequently used ways to describe them.

The first characters we see are workers climbing a structure. These are long-legged, thin figures with backpacks and helmets who climb endlessly without any apparent goal, but they all climb in repetitive and synchronous movements. It’s not until the last third of the film that they do anything other than this, and at first there is nothing to distinguish one worker from another. At this early stage, they serve a graphic function rather than an explicit narrative function, as the figures and movements repeat with little variation.

The second characters we see are what are often described as immortals, whose refined movements, dignified postures, and courtly appearance distinguish them as elites in Chronopolis. It’s not until late in the film that we understand that their height and stature also towers over the much smaller workers.

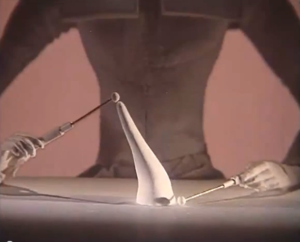

The first third of the film focuses on the immortals as they manipulate a malleable, multi-functional material using tools that resemble electrodes. Much of this first section, in fact, focuses on exploring the properties of this material, rather than developing much narrative momentum. The material seems to be crucial to the existence of Chronopolis, and to the god-like power of the immortals, because it can be transformed into almost anything.

Like the workers, the immortals are not particularly distinguished from each other, but unlike the workers they do have a degree of agency. Their agency, however, does not lead to an obvious goal for the narrative, other than the broad one of the ongoing existence of Chronopolis.

Like the workers, the immortals are not particularly distinguished from each other, but unlike the workers they do have a degree of agency. Their agency, however, does not lead to an obvious goal for the narrative, other than the broad one of the ongoing existence of Chronopolis.

This section is best described as organized by graphic and abstract principles: shape, movement, repetition, and variation. While there certainly is a plot, the main pleasure in this section comes from the musical composition of these graphic principles. Those who are expecting more narrative momentum are encouraged to focus instead on the visual textures and rhythms.

A repeated effect, resembling a series of prismatic wipes, fractures the image like a cubist painting. As the immortals manipulate the material and and it takes shape through space, the effect is often like an abstract animation by Norman McLaren (I’m thinking in particular of A Phantasy). When these abstract principles are appreciated, the film can often mesmerize.

In the last third of the film a worker falls from his climb, and this individual assumes the role of the protagonist. As he (I’ll assume male gender) wanders on top of a system of pipes in Chronopolis, he encounters a sphere made by the immortals out of the special material. Rather than being a threat to the worker (like the Rovers in The Prisoner), this sphere seems to provide the worker with an intoxicating, euphoric, and liberating experience. The immortals are not pleased about this development, and they dispatch drones to retrieve the worker and the sphere.

This last section follows a more clear narrative trajectory, as we now have a clear protagonist in the fallen worker and a clear conflict with the immortals. Kamler expertly expresses the emotions of the worker through subtle use of gesture and posture. Those looking for more narrative cues will find the last third of the film more interesting and engaging. Personally, I preferred the more abstract first half, which provided more space to explore the art direction and character designs.

In relation to the rest of the Rooftop series this summer, Chronopolis shares more in common with the obtuse mythopoeia of Naoyuki Tsuji than the audience-friendly abstraction of Karen Aqua (you can read my preview of those two past shows at Isthmus). But audiences who engaged with those previous screenings should be well prepared to appreciate yet another unique filmmaker with a distinct visual and storytelling style.