Attend: Program Notes

Attend: Program Notes

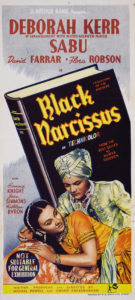

Black Narcissus | Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger | UK | 1947 | 101 minutes

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, December 1, 6:30pm»

In his program notes, Cinesthesia programmer Jason Fuhrman contrasts Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus with Rumer Godden’s original novel, and explains how objections from the Catholic Legion of Decency led to cuts for the American distribution of the film.

“It is the most erotic film that I have ever made,” wrote Michael Powell of Black Narcissus. “It is all done by suggestion, but eroticism is in every frame and image, from the beginning to the end.”

Adapted from a 1939 novel by Rumer Godden, the film follows five British missionary nuns as they attempt to establish a convent in the remote vastness of the Himalayas. But isolation, high altitude, culture clashes and the exotic atmosphere gradually erode their psyches. This enthralling, provocative study of the age-old conflict between the spirit and the flesh represents a creative peak in the fertile collaboration between Powell and writer Emeric Pressburger. It also remains among the most beautifully designed color films of all time. With its elaborate set, breathtaking photography, superbly nuanced performances, and psychological exactitude, Black Narcissus is a cinematic hothouse flower that achieves a nearly perfect fusion of all the elements of filmic art, while continuing to spellbind viewers after almost seventy years.

Despite its dazzling visual sweep, not a single frame of Black Narcissus was shot on location in India. Much to the surprise of his creative team, Powell felt that the film had to be made under controlled conditions. “The atmosphere in this film is everything, and we must create and control it from the start,” he said at the first production meeting for Black Narcissus. “Wind, the altitude, the beauty of the setting—it must all be under our control.”

The Palace of Mopu was constructed on sets at the Pinewood studios in suburban London. Production designer Alfred Junge meticulously created the Himalayas on stages and back lots, making extensive use of huge canvas backdrops painted with vibrant landscapes. Broader vistas, including the shots which establish the precarious cliff-side setting of the palace, were accomplished in post-production with glass shots and matte paintings executed by Peter Ellenshaw. Leonardslee, a complex of sub-tropical gardens in Horsham, Sussex, served as the lush valley below.

Cinematographer Jack Cardiff deliberately patterned his delicate lighting of the convent scenes after Vermeer, Rembrandt, and other painters. Cardiff’s contribution is noteworthy for his use of lower light levels than usual for Technicolor stock, which was notorious for the amount of light it required on set.

Cinematographer Jack Cardiff deliberately patterned his delicate lighting of the convent scenes after Vermeer, Rembrandt, and other painters. Cardiff’s contribution is noteworthy for his use of lower light levels than usual for Technicolor stock, which was notorious for the amount of light it required on set.

Author Rumer Godden (1907-1998) was born in Sussex, England. As a child Godden moved with her parents to India and lived in Assam and Bengal before returning to England to complete her studies. During the 1930s she began to publish her first novels, achieving a critical and popular breakthrough with Black Narcissus. Many critics have interpreted the novel in retrospect as a commentary on the ultimate failure of the British Empire’s colonial project in India.

Powell and Pressburger’s film retains the essentials of the book’s plot and dialogue, but it is very different in style and tone. The movie tends toward visually striking, at times melodramatic effects, whereas Godden’s prose style is notably cool and restrained. Godden declared after seeing Black Narcissus: “I have taken a vow never to allow a book of mine to be made into a film again.”

Nevertheless, it was only four years later when Jean Renoir shot the first Technicolor film made wholly in India, The River, based on another Rumer Godden novel about characters who are forced to accept unwelcome realities. (Godden herself loved the Renoir film, which she worked closely on, as much as she despised Black Narcissus.) But these are very different works made by very different artists. While the Renoir film has an almost documentary feel and an extremely loose narrative that emphasizes a broad continuum of existence, the Powell and Pressburger film is very tightly structured (much more so than the novel), with a clear beginning, middle, and end point.

In his essay on Powell and Pressburger’s film, Kent Jones writes, “The River is about the flow of life, while Black Narcissus is about the convulsive effect of life on closed minds, a drama of fugitive glances and grimaces and fixations, of gusts of wind and swaths of color and light, advancing in vivid and at times hair-raisingly precise emotional increments, each one as richly abundant and visually satisfying as the last.”

Black Narcissus was released in Great Britian on May 26, 1947 by the Rank Organization. Through Powell and Pressburger’s deal with Rank, the film was assured solid distribution in the United States, because Rank had entered into an agreement with Universal Studios in 1946. As it turned out, the film only had spotty distribution in America, due to censorship problems.

Black Narcissus was released in Great Britian on May 26, 1947 by the Rank Organization. Through Powell and Pressburger’s deal with Rank, the film was assured solid distribution in the United States, because Rank had entered into an agreement with Universal Studios in 1946. As it turned out, the film only had spotty distribution in America, due to censorship problems.

Powell and Pressburger were actually aware of the potential for censorship trouble in America before the film was shot. In April of 1945, a rough draft of the script was submitted to Joseph Breen at the Production Code Administration. Breen outlined his initial concerns to Rank: “While the story is not quite clear and concise, to us it has about it a flavor of sex sin in connection with certain of the nuns, which, in our judgment, is not good.” The Breen office, however, passed the finished film in June 1947, but on the condition that a foreword was added making it clear that the nuns were Anglo, rather than Roman Catholic.

Indeed, it was with the Catholic Legion of Decency that Rank encountered the most problems. The Legion of Decency launched a campaign against the film’s release as early as April 1946, when the Archbishop of Calcutta began writing about the production. Predictably, when the film was reviewed by the Catholic weekly The Tidings, published in Los Angeles, the judgment was harsh: “It is a long time since the American public has been handed such a perverted specimen of bad taste, vicious inaccuracies and ludicrous improbabilities.” When the Legion screened the film, it was given a “C” classification, or “Condemned”.

The Legion of Decency still held great sway over moviegoing habits in America, and a Condemned film would eliminate a huge number of ticket sales. Black Narcissus had already opened in New York and Los Angeles, but the ban interfered with scheduled openings in other cities, such as Detroit and Memphis. Furthermore, Parliament had just imposed a 75 percent duty on American films imported to England, and Hollywood was temporarily boycotting the British market. The few British films that could play well in America were encouraged as a goodwill gesture, so Rank was anxious that Black Narcissus play in as many American cities as possible. The only option they saw was to make cuts to the film to satisfy the Legion of Decency. So in September, 1947, the film was edited by 900 feet or so – ten cuts in all.

All of Sister Clodagh’s memories of Ireland (a key plot element) were cut, which accounted for most of the offending footage. The close-up of Sister Ruth applying lipstick was also eliminated, as well as a few lines of suggestive dialogue. Finally, the wording of the foreword was changed so that there would be no mistaking that the order of nuns might be Catholic; now it read: “a group of Protestant nuns in mysterious India find adventure, sacrifice, and tragedy.” The “C” was removed and the film was released with an “A2” classification, or “unobjectionable for adults.”