Attend: Program Notes

Antichrist | Lars von Trier | Denmark | 2009 | 108 min.

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, November 14, 6:30 p.m.

Lars von Trier’s apocalyptic experimental horror film Antichrist pushes the envelope of human emotions and takes filmmaking to another level.

“I would like to invite you for a tiny glimpse behind the curtain, a glimpse into the dark world of my imagination: into the nature of my fears, into the nature of Antichrist.”

Lars von Trier

Danish provocateur Lars von Trier’s apocalyptic experimental horror film Antichrist became a sensation when it premiered at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, eliciting derisive laughter, a smattering of applause, loud boos, and gasps of disbelief. The film shocked viewers, divided opinion, and made headlines due to the explicitness of its abject sexual violence. It also reportedly caused four people to faint. Antichrist has been called a “calamitous atrocity,” “easily one of the biggest debacles in Cannes Film Festival history,” and “the sickest general release in the history of cinema.” Variety labelled it “a big fat art-film fart.” For the critics at Time magazine, the movie “presented the spectacle of a director going mad.” Nevertheless, von Trier’s controversial, demanding, and enigmatic psychodrama offers much more than just a series of grotesque tableaux as it pushes the envelope of human emotions and takes filmmaking to another level.

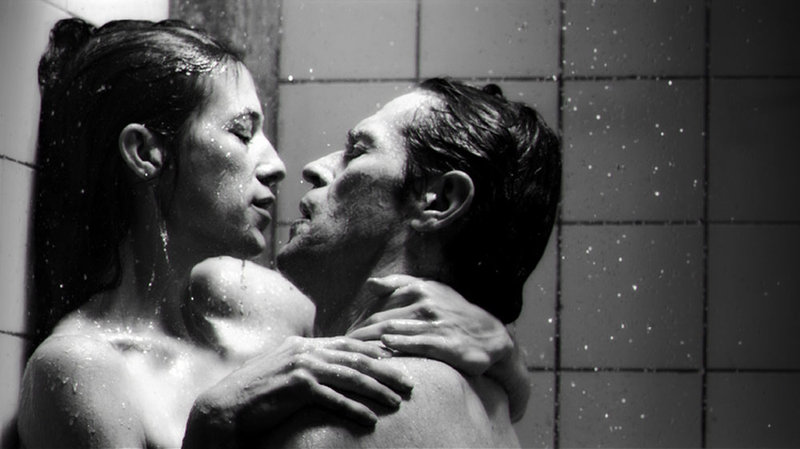

Antichrist opens with an elegant, dreamlike sequence of a couple, known only as He (Willem Dafoe) and She (Charlotte Gainsbourg), making love at home in slow motion. Their bodies are exhibited in luminous black-and-white photography to the accompaniment of Handel’s sublime aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” (“Let Me Weep,” from his opera Rinaldo), while snow falls outside an open window. This might be an upscale perfume ad, except for one X-rated shot. (The actors were doubled by porn veterans at such moments.)

All of a sudden, the couple’s infant son, Nic (Storm Acheche Sahlstrøm), gets out of his crib, observes his parents copulating, and climbs to the windowsill. He tumbles out, along with his teddy bear, and falls to his demise, at what seems to be precisely the moment of his mother’s climax. (Let us not forget that the French refer to orgasm as la petite mort.) The prologue fades out and the images switch to muted color.

After collapsing at the child’s funeral, the inconsolable mother finds herself hospitalized for one month. Her husband, who happens to be a rationalist cognitive therapist, insists that she discharge herself. He wants to take over her treatment and believes that She must confront her greatest fears. The grieving couple retreat to “Eden,” their remote mountain cabin deep the woods, where they hope to repair their broken hearts and troubled marriage. As the natural world becomes increasingly ominous and strange, He and She begin to inflict pain on one another in unspeakable and startlingly intimate ways. Ultimately, the husband’s program of counseling and role-play therapy gives way to a fierce, life-and-death struggle.

An audacious, breathtaking combination of marital melodrama, hard-core pornography, gothic horror, and avant-garde experimentation, von Trier’s film derives its title from Friedrich Nietzsche’s 1895 book The Antichrist, which was published shortly before the author’s mental breakdown. The director claims to have kept a copy on his bedside table since he was twelve and simply says, “I started with the title.”

According to von Trier, the film was written as a form of therapy in the midst of a deep depression when “Everything, no matter what, seemed unimportant, trivial.” Antichrist was a test to see if he would ever make another film. He admits to not being very aware of what he was doing when he wrote the movie.

“The work on the script did not follow my usual modus operandi,” von Trier explains. “Scenes were added for no reason. Images were composed free of logic or dramatic thinking. They often came from dreams I was having at the time, or dreams I’d had earlier in my life.” No wonder, then, that the finished product seems so raw and emotionally charged, at times absurd and on the verge of complete disorder. Recalling the work of artists such as David Lynch, Antichrist feels like a direct feed into the subconscious.

Alternating between striking, formally rigorous compositions and a loose, naturalistic, documentary-like visual style, von Trier immerses us in a desolate, ethereal landscape that seems to exist outside of space and time. He strips the plot down to its bare necessities and conveys his story primarily through a chain of evocative images, fleeting impressions, and vague ideas. An uneasy sense of foreboding pervades the film as the environment of Eden becomes increasingly unnatural and hostile. These peculiar occurrences appear to mirror the wife’s mental state and accelerate the disintegration of the couple’s relationship. Throughout this vivid waking nightmare, von Trier touches on an impressive array of themes and issues, providing a fertile ground for practically endless analysis, even as the film actively resists interpretation.

With its apocalyptic visual richness, defiantly excessive flourishes of violence, vast psychological acuity, and fearless, utterly convincing performances, Antichrist jolts the spectator out of passive viewing, while cutting to the core of what makes human existence painful. Von Trier creates an unflinching portrait of a dysfunctional marriage as he revises familiar horror movie tropes to make us feel the genuine horror of facing our buried fears and conflicts. Although the film’s graphic depictions of bodily harm are incredibly intense and grueling to watch, Antichrist cannot be easily dismissed as empty sensationalism. As long as we are not too distracted by the gore, we may recognize the artistic merit of a work that illuminates the darkest corners of the human psyche, while exploring the visual possibilities of cinema in unprecedented and dazzling ways. Critic Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, defends its more objectionable moments:

These passages have been referred to as “torture porn.” Sadomasochistic they certainly are, but porn is entirely in the mind of the beholder. Will even a single audience member find these scenes erotic? That is hard to imagine. They are extreme in a deliberate way; von Trier, who has always been a provocateur, is driven to confront and shake his audience more than any other serious filmmaker — even [Luis] Buñuel and [Werner] Herzog. He will do this with sex, pain, boredom, theology and bizarre stylistic experiments. And why not? We are at least convinced we’re watching a film precisely as he intended it, and not after a watering down by a fearful studio executive.

In his 2012 book Film After Film: Or, What Became of 21st-Century Cinema?, film critic J. Hoberman cites Antichrist among examples of what he terms “experiential cinematic ordeals.” Likewise, Amy Simmons, in her study of von Trier’s film for the Devil’s Advocate book series, acknowledges that “Antichrist isn’t a work to love. It is a work to admire, to puzzle through and to wrestle with.” The film may be designedly provocative, but not simply for shock value. Rather, Antichrist demands active spectatorship as von Trier reveals the innermost recesses of his imagination. Simmons maintains that Antichrist transcends the label of “torture porn” because of the emotional journey it guides us on, wherein “the first goal of von Trier’s project [is] to elicit a truthful emotional response from the viewer. By privileging the spectator’s instinctual, visceral responses, von Trier deliberately shatters our complacency.” Dense, ambiguous, and haunting, von Trier’s film dares us to probe beneath the surface to discover the true nature of Antichrist.

In an essay for the Criterion Collection release of Antichrist, film scholar Ian Christie begs the question:

What are we to make of this bloody and seemingly perverse, yet highly sophisticated, tale? On my first viewing, I was in such a state of shock that I barely registered the final dedication to Andrei Tarkovsky, let alone a curious group of credits meticulously recording research carried out on misogyny, mythology and evil, anxiety, horror films, theology, and therapy.

At once a profoundly disturbing look at (human) nature, an intensely personal work of transgressive art, a lurid descent into the most feverish depths of female sexuality, a painstakingly crafted horror thriller, and a film essentially about its own making, Antichrist envelops the viewer by opening up a multitude of possible meanings. Is von Trier’s creation a work of genius or the sickest film ever made? Perhaps both.