Hitchcock Week: Part Two of Five

Hitchcock Week: Part Two of Five

This week the Madison Film Forum will present reflections on the next five films in the UW Cinematheque’s Hitchcock Masterworks series. These are not intended as reviews for readers who have not seen the films. We hope they will serve as the start of a conversation with those who have seen the films and will be revisiting them at the UW Cinematheque series, or through the streaming resources linked at the end of the entries.

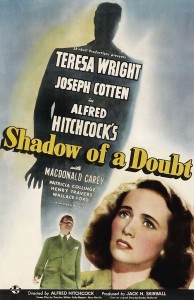

Our next installment sees regular contributor Jake Smith discussing Shadow of a Doubt (1943), which will play at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, February 16 at 2:00 pm.

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

During the 2012 Wisconsin Film Festival, experimental filmmaker Phil Solomon lamented the usual way that dissolves are used in most Hollywood films. He talked about what a beautiful cinematic technique the dissolve is at a basic level, and how it was mostly used merely as simple transition with little or no impact, except to convey passage of time. Along with many other things he discussed during those screenings, that one has stayed with me.

During the 2012 Wisconsin Film Festival, experimental filmmaker Phil Solomon lamented the usual way that dissolves are used in most Hollywood films. He talked about what a beautiful cinematic technique the dissolve is at a basic level, and how it was mostly used merely as simple transition with little or no impact, except to convey passage of time. Along with many other things he discussed during those screenings, that one has stayed with me.

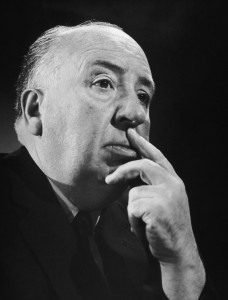

Shadow of a Doubt is easily one of my favorite Hitchcock films for many reasons. When considering some of the more typical of the Hitchcock formula, it appears anomalous. There’s no “macguffin” or “wrong man”; indeed, in terms of guilt, Joseph Cotten’s Charlie Oakley is very much the right man. Cotten, who at the time I knew only from his work in Citizen Kane and The Third Man, shattered my perception of him as an actor who excelled at playing almost pathetically moral characters, turning in a performance of commandingly calm menace. But on a stylistic level, I love the way Hitchcock uses the dissolve to achieve a singular combination of nostalgia and creepiness.

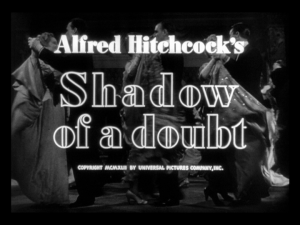

Bereft of context, the titles for the film are quite confusing at first, and we don’t see those images again until more than 20 minutes into the film. Once we do, that shot is sandwiched just briefly between two dissolves. We first see Joseph Cotten following Teresa Wright back to the dinner table.

Bereft of context, the titles for the film are quite confusing at first, and we don’t see those images again until more than 20 minutes into the film. Once we do, that shot is sandwiched just briefly between two dissolves. We first see Joseph Cotten following Teresa Wright back to the dinner table.

The frame dissolves to the same waltz from the titles…

…and then another dissolve back to the dinner table, with hardly any time at all passing.

Superimposing the image of the waltz at the time Cotten is closest to the camera gives it an impression of memory and enhances the general feeling of nostalgia that has already been so well established by the script. For those of us who may not know “The Merry Widow Waltz” right away, the repetition of a shot that seems otherwise out of place in the action also enhances the anxiety that Cotten leaves in his wake through every scene. It’s revisited throughout the picture—always positioned between two dissolves, and always to beautifully unsettling effect as the precise mania of Cotten’s character becomes clear.

Superimposing the image of the waltz at the time Cotten is closest to the camera gives it an impression of memory and enhances the general feeling of nostalgia that has already been so well established by the script. For those of us who may not know “The Merry Widow Waltz” right away, the repetition of a shot that seems otherwise out of place in the action also enhances the anxiety that Cotten leaves in his wake through every scene. It’s revisited throughout the picture—always positioned between two dissolves, and always to beautifully unsettling effect as the precise mania of Cotten’s character becomes clear.

Certainly there are other examples of dissolves used to effect beyond the typically transitory, but Hitchcock’s use in this film has always stuck with me, along with everything else about the film. It lacks the hyperstylized quality of some of the later films, opting instead for a more direct approach. Its small town setting is every bit as compelling as the more extravagant locales from other films. It has a very nearly perfect cast, “with the exception of the detective,” as François Truffaut wrote, referring to Macdonald Carey (whom Cinematheque patrons may remember as Nick Carraway from the 1949 version of The Great Gatsby) as the film’s sole standout bore. The film’s humor is also every bit on par with much of the director’s prior British work, especially every time Henry Travers and Hume Cronyn break off into a conversation about murder.

Something else that has stuck with me is one last thing Phil Solomon said while he was in town. He talked about the wonder that accompanies the notion of “attending” someone’s work. To go into a space designed expressly for the exhibition of that work—to give it its due attention and (hopefully) enjoy a simultaneously personal and communal experience—is part of what going to the movies is all about. It is what institutions like the Cinematheque are designed to do, and it is giving us the chance with a 35mm print of Shadow of a Doubt this coming Sunday. Having never seen this film on the big screen, I can’t wait to be among those in attendance.

In addition to the February 16 screening at the UW Cinematheque Hitchcock Masterworks series, Shadow of a Doubt is also available to rent from Amazon Instant Video and Vudu: