Attend: Program Notes

Bamboozled | Spike Lee | United States | 2000 | 135 min.

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, March 7, 6:00 p.m.»

Spike Lee’s overlooked 2000 satire Bamboozled remains in constant dialogue with the world of today, while demonstrating that media representation of race has never been a black and white issue.

Arguably Spike Lee’s most confrontational, groundbreaking, and misunderstood movie, Bamboozled has long been dismissed as little more than a mid-career curiosity in the filmography of the prolific, seminal director. A bizarre, caustic, multifaceted satire of American television, this timelessly important piece of experimental filmmaking examines the complex relationship between race and popular culture in an emotionally provocative and intellectually stimulating manner. In the 2012 book Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop, Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen begin a chapter on the film as follows.

The screen has never been as bold, as powerful, or as angry a response to the black minstrel tradition as Spike Lee’s 2000 feature Bamboozled. The movie is a vehement damnation of black minstrelsy, a presentation of some of the art form’s best moments, and perhaps most valuably, a vividly illustrated catalogue of some of the greatest hits, misses, and embarrassments of American cinema’s adoption of the form. In the years since its initial release Bamboozled has introduced fresh eyes and minds to shocking images and practices, and provided students of this complicated cultural history a useful tool to spark discussion, debate, and scholarship. It would be impossible to thoroughly study black minstrelsy and its impact on contemporary culture without lingering on this mesmerizing work.

Lee’s absurdist black comedy shines light on historical truths that many people either are ignorant of or would prefer to conveniently forget. At the same time, his film suggests that racial stereotypes from that supposedly bygone era are still deeply embedded in mainstream entertainment, even if actual blackface minstrelsy does not persist. In a 2001 interview with Cineaste editors Gary Crowdus and Dan Georgakas titled “Thinking about the Power of Images,” Lee explains that in Bamboozled he wanted to “show that from their birth these two great mediums, film and television, have promoted negative racial images.” The director proceeds to assert that “Racism is woven into the very fabric of American society, and it just makes sense that it’s going to be reflected in sports, in movies, in television, in business, and so on.”

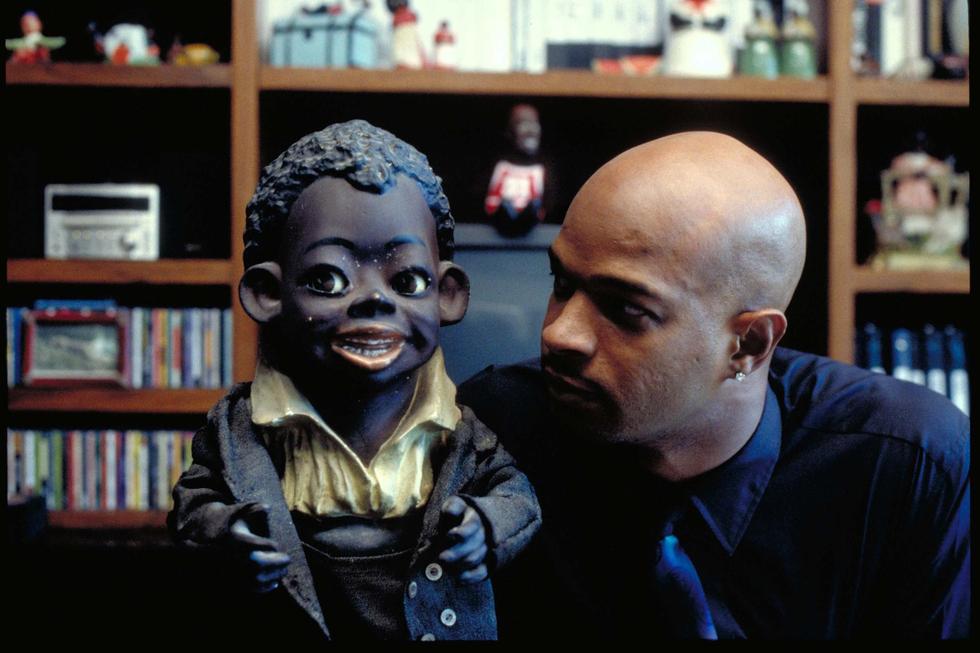

Bamboozled centers on the meteoric rise and inevitable downfall of Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans), a pretentious, Harvard-educated, and upwardly mobile black executive for a struggling television network. His vulgar, entitled white boss, Dunwitty (Michael Rapaport), continuously demands fresh, cutting-edge, authentically black material, while rejecting Delacroix’s ideas for aspirational black middle-class sitcoms. Artistically frustrated and weary of his job, Delacroix, or Dela, devises a risky scheme to get himself fired.

He conceives a grotesque vaudeville show—set on a watermelon patch—in which black actors wear ludicrously exaggerated blackface makeup, while singing, tap dancing, chattering nonsensically, telling crude jokes, and pilfering chickens. Dela believes his project, called The New Millennium Minstrel Show, in its flagrant racial excesses and distortions, will expose the racism of the white writers and producers.

With the help of his smart, skeptical assistant Sloan Hopkins (Jada Pinkett Smith), Delacroix recruits two homeless street performers, Manray and Womack (Savion Glover and Tommy Davidson), to star in the production. He rechristens them Mantan and Sleep ‘n’ Eat (borrowing names from minstrelsy-inspired movie actors Mantan Moreland and Willie “Sleep ‘n’ Eat” Best). The Alabama Porch Monkeys serve as the house band (in a cameo by the masterfully dexterous, musically brilliant Philadelphia act The Roots).

To Delacroix’s bewilderment, his program largely fails to excite popular outrage and becomes an instant smash hit. As its ratings go through the roof, The New Millennium Minstrel Show revives the network, earns its creator some Emmy Awards, and starts a national craze for wearing blackface. The show stirs some controversy, of course, resulting in public protests outside its corporate headquarters led by the Reverend Al Sharpton and lawyer Johnny Cochran (appearing as themselves). It also attracts the ire of the Mau Maus, a militant Afrocentric rap collective headed by Sloan’s brother, Julius (played by socially conscious rapper turned actor Mos Def). Named for the legendary Kenyan Mau Mau that organized a dramatic rebellion in 1952 against British colonialism, the illiterate, misguided group espouses vapid, pseudo-revolutionary politics and suggests a ridiculous hybrid of Public Enemy and the Black Panthers.

All too aware that he has hatched a monster, Delacroix nevertheless finds himself seduced by the promise of fame and fortune after working so hard to succeed within the predominantly white entertainment industry. But Dunwitty adopts the minstrel show idea as his own and makes it even more degrading, if possible, than Delacroix had intended. Through his complicity in perpetuating pejorative racial stereotypes on The New Millennium Minstrel Show, Delacroix descends into a downward spiral, while setting in motion a chain of events that has dire consequences for him and everyone else involved. Consumed by guilt, paranoia, and self-hatred, he ultimately faces the harsh realities of American racism.

The germ of the idea for Bamboozled was a film called The Answer that Lee made as a student at the prestigious New York University Film School. Lee shocked his professors and inflamed the first of many audiences with this twenty-minute, black-and-white short about a young African-American screenwriter hired to direct a big multimillion-dollar Hollywood remake of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). “This guy sells his soul to the devil to do that film,” Lee explains. “And we intercut the film with some of the worst racist scenes from the so-called greatest film ever made. Bamboozled revisits that, because if you look at that character in The Answer and at Delacroix in Bamboozled, there are various similarities.”

The title comes from a Malcolm X speech warning that black people have let themselves be deceived by the white man, which Lee references in his 1992 biopic of the celebrated and influential black nationalist leader: “Oh, I say and I say it again, you’ve been had! You’ve been took! You’ve been hoodwinked! Bamboozled! Led astray! Run amok!” But Lee affirms that Bamboozled is not just about black Americans. “I think we were expanding on the speech and saying, ‘Don’t believe everything you…see on television.’”

Bamboozled owes a considerable debt to Melvin Van Peebles’ documentary Classified X (1998) in exposing the way in which African-Americans have historically been portrayed in American cinema. Lee was “amazed” by the imagery in that work, so he contacted the film’s researcher, Judy Aley, to obtain archival material for Bamboozled. He recalls, “None of us had seen this material. For example, I had never seen Bugs Bunny in blackface! Unfortunately, Time Warner would not allow us to use that clip because Bugs Bunny is too valuable a commodity to them, and they didn’t want the world to see that.”

In interviews and publicity, Lee has cited three films that skewer the American mass media as direct inspiration for Bamboozled: Sidney Lumet’s 1976 satire Network, Mel Brook’s 1968 farce The Producers, and A Face in the Crowd (1957) by director Elia Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg. As Lee put it, “everything that Budd Schulberg wrote about in 1957 about the power of television—this before people even knew what television was about—happened. Budd had the crystal ball and saw that TV would rule and whoever controlled that stuff would be running things.” (Lee dedicated Bamboozled to Schulberg.)

As in Brooks’s comedy about a play (with the title “Springtime for Hitler”) designed intentionally to flop, Delacroix creates a show that seems guaranteed to fail spectacularly, but his subversive plan backfires. Along with some overt textual references to Network (most notably Manray recalling Peter Finch’s iconic speech by declaring onstage, “Cousins, I want you to go to your windows, yell out, scream with all the life you can muster up inside your bruised and assaulted bodies, ‘I’m sick and tired of niggers and I’m not going to take it anymore!’”), Lee borrows that film’s drastic tonal shifts between comedy and drama.

The bold, controversial subject matter of the film’s script, as well as Lee’s recent commercial record, meant that the director had trouble raising the budget he wanted to make Bamboozled. Nevertheless, Lee has always figured out how to get his movies made—by any means necessary—and the means at his disposal when he shot Bamboozled in 1999 was digital video.

“We decided to shoot in DV early on, as the script was written,” Lee recalls. “We knew that getting this film made would be a very hard task.” Lee and director of photography Ellen Kuras did many tests with different cameras and formats of video. They did not like the look of Beta, DigiBeta, or high definition, and went with MiniDV, using a battery of Sony VX1000 cameras. “With this film it makes sense because it was about a television show,” Lee says. “And we also had a 132-page script and not a lot of days. . . . We were able to shoot eight, nine, ten cameras at a time. And it enabled us to put in the run-and-gun offense. So we were able to just shoot.”

Lee and Kuras decided to shoot The New Millennium Minstrel Show on vibrant Super 16mm film to give it a different look from the rest of the movie. In contrast to the harsh, pixelated textures of the digital scenes, the richly detailed footage of the show is presented with oversaturated colors that lend these sequences a lurid and seductive quality. (Filmmaker Zeinabu irene Davis has written that these scenes demonstrate the African-American cultural concept of “beautiful-ugly.”) In the words of Taylor and Austen, “The shiny, greasy-looking, pitch-black makeup, glistening blood-red lips, and beads of sweat breaking through the sinister masks make the ominous nature of the minstrel show viscerally obvious.”

In “Race, Media and Money: A Critical Symposium on Spike Lee’s Bamboozled,” published in Cineaste, Cynthia Lucia’s analysis of the film poses two probing questions: “To what degree do viewers participate in the very processes they are positioned by the film to criticize? And to what degree does the film, itself, participate in the very processes it seeks to expose?” On the one hand, Bamboozled educates the viewer about the very explicit derogatory stereotypes of African-Americans initiated during the era of minstrel shows (mid-19th to early 20th century) and sustained, as Lee pointed out at a March 21, 2008 talk at Northeastern University, until the present day. On the other hand, Lee creates a highly amusing pageant of traditional minstrel show entertainment. The film deconstructs racial stereotypes, even as it exploits racial stereotypes for their entertainment value, thus sending contradictory signals to viewers.

Bamboozled further complicates the viewing of negative racial images by daring us to laugh at the jokes. Watching the movie with other people can certainly make for a unique, albeit uncomfortable, cinematic experience. Lee acknowledges some ambiguity in the response to the kind of humor used in his film. He tells Crowdus and Georgakas, “We wanted to put the moviegoing audience in the same position as the TV audience in the movie. It’s funny, but they’re thinking, ‘Wait a minute. Should I be laughing at this?’”

At one point in Bamboozled, Lee cuts to an image of one of the insurgent Mau Maus laughing at a televised minstrel routine. Chastised by Julius (a.k.a. “Big Blak Afrika”), the offender replies, “That shit seemed funny to me.” Lee insists that “some of this stuff—despite how much hatred is behind it, and despite how painful it can be—is funny, and the reason it’s funny is because of the genius of the artists, of the performers who are able to make it funny even within that context. That’s the irony—that these artists were so great that they could take a dehumanizing form and still make it somewhat humanistic.”

The film offers viewers an authentic look at the conflicted emotional responses of the performers who must “black up” before going on stage. “The reality of putting this stuff on their face was devastating for Tommy Davidson and Savion Glover,” Lee reveals. “It took away part of their soul, it took away part of their manhood, and it made us think of Bert Williams. Tommy and Savion did it for a couple of weeks, but Williams had to do that his entire career.” Lee’s commentary on the DVD release points out that Davidson has a moment of insight as he applies the final touches to his blackface and cries “real tears.”

Bamboozled exempts no one from criticism for the continuing promulgation of crass racial stereotypes. Lee’s movie successfully indicts guilty parties at every level of media production and consumption for negative depictions of African-Americans in popular culture: past and present performers, the studios, black and white executives, and passive audiences. For Jada Pinkett Smith, this was the heart of the film:

Making this movie, we were all pointing fingers at ourselves in a way. It was really an exploration of “What do we represent in this business? Who are we? What compromises and sacrifices are we willing to make of our commitment to our higher selves and our community and our humanity? What are we doing in this industry that uplifts our community, and what are we doing that breaks it down for the sake of celebrity and money?”

With two commercial interludes that appear during the initial broadcast of The New Millennium Minstrel Show, Lee critiques the manner in which advertisers sell products to African-American consumers, cheap alcoholic beverages and Tommy Hilfiger clothes being the main targets. These hilariously crude parodies are reminiscent of Putney Swope, Robert Downey’s 1969 cult classic about race and truth in advertising, in which a token black executive becomes the new chairman of a major white advertising agency and proceeds to air a series of surrealistic, politically incorrect commercials. In Bamboozled, an ad for Da Bomb, a new brand of malt liquor (or “that liquid crack,” as Lee refers to it), promotes its product as an African-American aphrodisiac, a “black man’s Viagra” that helps you “get your freak on” with a phallic bottle shaped like a weapon of mass destruction. The other ad, for Timmi Hillnigger clothing, mocks the popularity of Tommy Hilfiger’s all-American clothing line within the black urban community. (“We keep it so real, we give you the bullet holes.”) Whereas Hilfiger features the patriotic colors of red, white, and blue, the backdrop in this commercial displays the Republic of New Africa colors of red, black, and green.

Eventually Lee’s satire ceases to be funny and becomes more like a horror film. As Bamboozled reaches its conclusion, Lee presents viewers with a powerful montage of images from the history of television and movies now considered offensive. This astonishing coda, underscored by soft cool jazz music, features some of America’s earliest films (including American Mutoscope’s 1901 short Laughing Ben); excerpts of Hollywood’s most iconic movies (The Birth of a Nation, Gone With the Wind, The Jazz Singer); white superstars in blackface (Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, Eddie Cantor); comic black actors in stereotypical roles (Butterfly McQueen, Farina Hoskins, Stepin Fetchit); cartoons from the first half of the 20th century; documentary footage of soft shoe and tap; and old newsreels of watermelon-eating contests. In “Spike Lee’s Revolutionary Broadside,” S. Landau argues that “Lee has done in one film more to enlighten audiences on race, class, history and entertainment than Hollywood has done in a century.”

A difficult, uncompromisingly feel-bad movie that requires several viewings to appreciate, Bamboozled predictably met with critical and commercial indifference upon its theatrical release. Ugly in both form and content, the film confused black and white audiences alike, grossing only $2.5 million on a budget of $10 million. There was a basic DVD release of Bamboozled in 2001, but it has been out-of-print for years.

At the turn of the millennium, many critics suggested that Lee had needlessly reopened old wounds and completely missed the point of the film. Chicago Reader‘s Jonathan Rosenbaum described it as “sloppy, all-over-the-map filmmaking with few hints of self-criticism,” while Roger Ebert found Lee’s film to be“perplexing” and predicted that “viewers will leave the theater thinking Lee has misused” black images. Andrew Sarris of the New York Observer called his attempt to turn blackface into satire “miscalculated.” Armond White, one of film criticism’s few prominent black writers, slammed it in the New York Press with “Bamboozled resembles a padded cell with which Hollywood has provided Lee to bounce off walls.”

The poor critical response to Bamboozled had Lee lamenting, “Some people misinterpreted the film, thinking it’s only about black people. Bamboozled is about the dehumanization and the degradation that comes via television and film.” Yet the ensuing years have seen Lee’s vision earn the respect it deserves.

Ashley Clark, film curator, critic, and author of Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, considers the movie a quintessential Spike Lee joint. “There are certain things that define Spike Lee as a filmmaker: a lack of subtlety, a fondness for caricatures, an interest in very hot-button social issues, formal and technological experimentation. Those things all crash together in Bamboozled.”

Lee’s flawed, ambitious, inflammatory, and altogether fascinating work of art has proven not only vital, but alarmingly prescient. Clark maintains that “In a fraught contemporary climate where the mediation of the black image in American society is at a crucial juncture, Bamboozled’s trenchant commentary on the importance, complexity and lasting effects of media representation could hardly feel more urgent.”

This screening is presented in collaboration with the inaugural Black Arts Matter Festival. A moderated discussion will follow the movie.