Attend: Program Notes

Attend: Program Notes

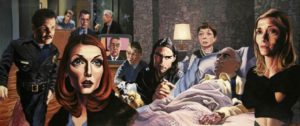

Magnolia | Paul Thomas Anderson | US | 1999 | 188 minutes

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, January 4, 5:30pm»

In his Cinesthesia program notes, Jason Fuhrman suggests that the bold stylistic flourishes on display in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia reflect a filmmaker at a turning point in his artistic development.

A dazzling, ambitious, kaleidoscopic and multifaceted mural of American lives on the verge of the new millennium, Magnolia immediately pulls viewers in and refuses to let go.

Epic in scale yet meticulously observed, the film interweaves the stories of nine major characters as they struggle to find solace, meaning, and happiness over the course of twenty-four hours California’s San Fernando Valley.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s flawed, florid masterpiece unfurls with exhilaratingly frenetic visual flair as Anderson introduces a diverse assemblage of lost souls. Gradually, the movie crystallizes and reveals how all of these characters are connected by blood, coincidence, and the way their lives reflect one another.

Anderson intertwines an impressive multiplicity of plots to tell one story, while sustaining a tone of heightened melodrama and touching on various themes, such as death, abandonment, exploitation, adultery, child abuse, identity, forgiveness, regret, masculinity, self-destruction, and love. The myriad threads converge, in one way or another, on a surreal occurrence near the end of the film. With its complex, densely populated narrative structure, unanimously stellar performances, dynamic visual style, technical audacity, and unapologetic excesses, Magnolia stands as one of Anderson’s most compassionate, intelligent, and challenging creations.

Despite the willful arbitrariness of Anderson’s approach, the film exerts a raw, cathartic power as it overwhelms our senses and emotions. The beautiful imperfection of Magnolia derives from his sheer confidence, his great skill with actors, his extraordinary intuition, and his talent for weaving resonant individual vignettes into ravishing patterns. With this sprawling, intimate epic he aspires to something beyond entertainment, and keeps us transfixed for more than three hours.

Film critic David Thompson deems it “his most youthful and indulgent film.” Indeed, there are multiple moments in the movie that come precariously close to pretension. Yet such indiscretions may be excused as the bold stylistic flourishes of a truly gifted, visionary filmmaker at a turning point in his artistic development who occasionally overreaches himself.

Written and directed by Anderson when he was only 28, Magnolia was a reaction to his previous film, Boogie Nights (1997). He never intended it to become such a big movie. In an exclusive interview with John Patterson for The Guardian, the director explains how Magnolia ripened into something else.

It came from a much smaller plane. I wanted to make something that was intimate and small-scale, and I thought that I would do it very, very quickly. The point was that I wanted to shed myself of everything that was happening around Boogie Nights. And I started to write and well, it kept blossoming. And I got to the point where still it’s a very intimate movie, but I realized I had so many actors I wanted to write for that the form started to come more from them. Then I thought it would be really interesting to put this epic spin on topics that don’t necessarily get the epic treatment, which is usually reserved for war movies or political topics. But the things that I know as big and emotional are these real intimate everyday moments, like losing your car keys, for example. You could start with something like that and go anywhere.

Anderson’s scripts, he says, start out as “lists of things that are interesting to me, images, words, ideas, and slowly they start resolving themselves into sequences and shots and dialogue.” For Magnolia, he first saw an image of the smiling face of his friend, actress Melora Walters, and proceeded from there.

New Line producer Michael De Luca promised Anderson complete creative control without even hearing an idea for the movie. The director seemed to understand that he would never be in this position again. Because of his special privilege, he was free to make his most personal film to date. “I consider Magnolia a kind of beautiful accident,” he explains to Lynn Hirschberg in the New York Times Magazine. “It gets me. I put my heart—every embarrassing thing that I wanted to say—in Magnolia.”

The initial cut of the film was 3 hours, 18 minutes, and he refused to trim it down. “You have to sit in the movie and really absorb it,” Anderson explains. “I am always looking for that nuance, that moment of truth, and you can’t really do that fast. I was trying to say something with this film without actually screaming the message. Although three hours may be something of a scream, I wanted to hold the note for a while.” While Magnolia may be difficult at times, Anderson proves that art and commerce can coexist, that a unique, properly packaged three-hour film can actually captivate mainstream audiences.

(In 2015, Anderson admitted to Marc Mahon that he would cut the film differently if he made it today. “I wasn’t really editing myself,” he says. “It’s way too fucking long.”)

Magnolia invites comparisons to Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993) for its mosaic approach to storytelling. Altman is one of Anderson’s most influential mentors. It is perhaps not coincidental that both films have a run time of exactly 188 minutes, feature Julianne Moore, and reach an apocalyptic climax.

Film critics were torn about Magnolia: generally awed by its technical audacity, narrative sophistication, and nuanced performances, but hesitant to fully endorse it. Sight and Sound’s Mark Olsen calls Magnolia “a grandiosely sprawling, audaciously earnest concoction…a magnificent train wreck of a movie.” Kenneth Turan at The Los Angeles Times concludes: “[a] frantic, flawed, fascinating film that is both impressive and a bit out of control, often at the same time, Magnolia may occasionally overshoot its mark, but it’s the kind of jumble only a truly gifted filmmaker can make.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum at the Chicago Reader describes the film as “a wonderful mess.” Rosenbaum later conceded that it needs to be seen more than once and now regards it as “Anderson’s best film to date, as well as his most coherent.” At the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert praises it as “the kind of film I instinctively respond to. Leave logic at the door. Do not expect subdued taste and restraint, but instead a kind of operatic ecstasy.” Ebert included Magnolia in his list of “Great Movies” in November 2008.

During an interview for the Swedish paper Sydsvenska Dagbladet, filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, of all people, cited Magnolia among “fine examples of the strength of American cinema.”