Attend: Program Notes

The Long Goodbye | Robert Altman | United States | 1973 | 112 min.

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, March 21, 6:30 p.m.»

Robert Altman’s highly original, amusing adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye casts a critical eye on the classic hard-boiled detective noir genre, while offering trenchant commentary on the shift in American values after the 1960s.

In a 2015 review of the Blu-ray release of The Long Goodbye for Cineaste magazine, Rahul Hamid writes:

Film noir is a slippery term. It doesn’t really represent a consciously produced genre, like the Western or the musical. It is a mood and a style and a preoccupation with dark themes that can be found in some, but certainly not a large percentage, of Hollywood films of the Forties and Fifties. It might be historically contingent on the flood of German émigrés—trained in the expressionist style—that came to Hollywood in Hitler’s wake. It can be contextualized by the loss of innocence experienced by GIs who witnessed the horrors of the war, or insecurities at home based on the expanding presence of women and minorities in the workforce and American public life, or the expansion of American cities and the housing crunch caused when veterans returned home. The explanation might be as mundane as the invention of cheaply produced metal venetian blinds in the 1940s. Some argue that it is the existence of neo-noir, or the collective memory of noir, that gives the original movement any real coherence. Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is a contemplation of the memory of Hollywood and an invitation to interrogate the values of and reassess our nostalgia for that great dream factory.

Based on the hard-boiled 1953 novel by Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye offers an idiosyncratic, revisionist take on film noir and the detective genre. Maverick director Robert Altman playfully updates Chandler’s story to the 1970s, “transforming it into a dreamlike excursion through modern Los Angeles,” in the words of Alan R. Howard, who reviewed the movie for The Hollywood Reporter when it came out.

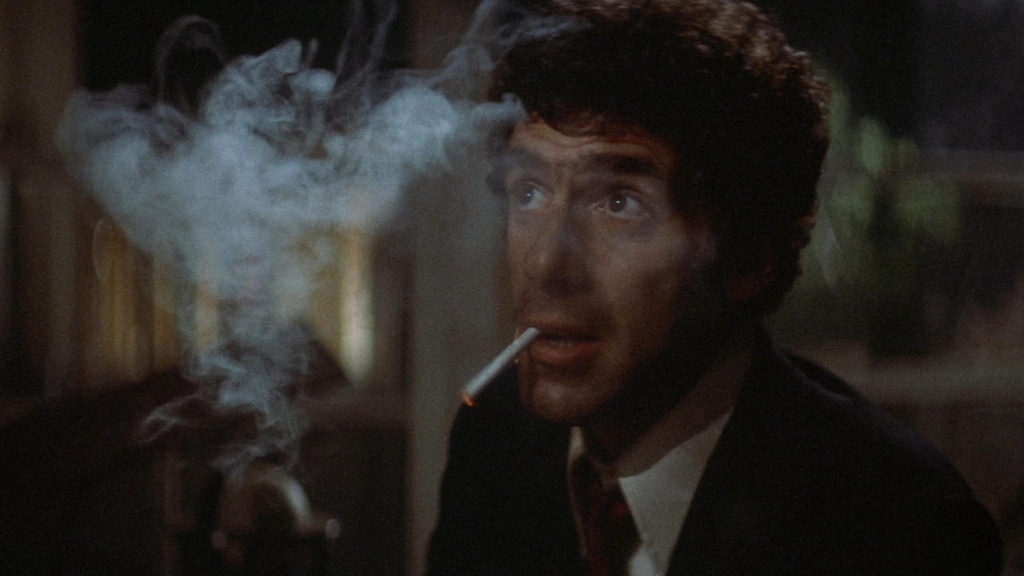

In stark contrast to the tough, no-nonsense leading men usually cast as Chandler’s legendary private eye Philip Marlowe, most memorably Humphrey Bogart in Howard Hawks’ 1946 adaptation of The Big Sleep, Altman chose laid-back, amiable Elliott Gould for the starring role. Gould remodels the character into an eccentric, bungling, clueless hipster who chain smokes, while repeating the mantra, “It’s OK with me.” Always dressed in a dark suit and tie and driving a 1940s Lincoln, Gould’s Marlowe represents a walking anachronism. He seems to be the last moral and decent person in a materialistic, self-absorbed society where human lives are disposable and any concepts of loyalty or friendship are essentially meaningless.

Working from a screenplay by Leigh Brackett (who also co-wrote Hawks’ The Big Sleep), Altman makes a number of changes to Chandler’s book, while remaining relatively faithful to the plot. Although The Long Goodbye eschews the violent sequences of both the original novel and earlier adaptations of Chandler’s work (no punch-ups or shoot-outs), it contains two shocking scenes of brutality that are not in the book.

Altman has admitted that he never actually finished reading The Long Goodbye. With the adaptation, he and Brackett attempted to reflect more on the author than on his story. The making of the movie was influenced by a volume called Raymond Chandler Speaking (edited by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker), a collection of excerpts from letters, notes, essays and an unfinished novel by the writer. Divided into various themes, the book includes a section on Chandler’s love of cats. Thus, Altman’s film famously opens with a sequence that does not appear in the original novel. Marlowe attempts to trick his yellow tabby cat into eating an inferior brand of cat food, but the feline immediately sees through the deceit. Alas, the private detective does not possess the same powers of discernment as his pet cat.

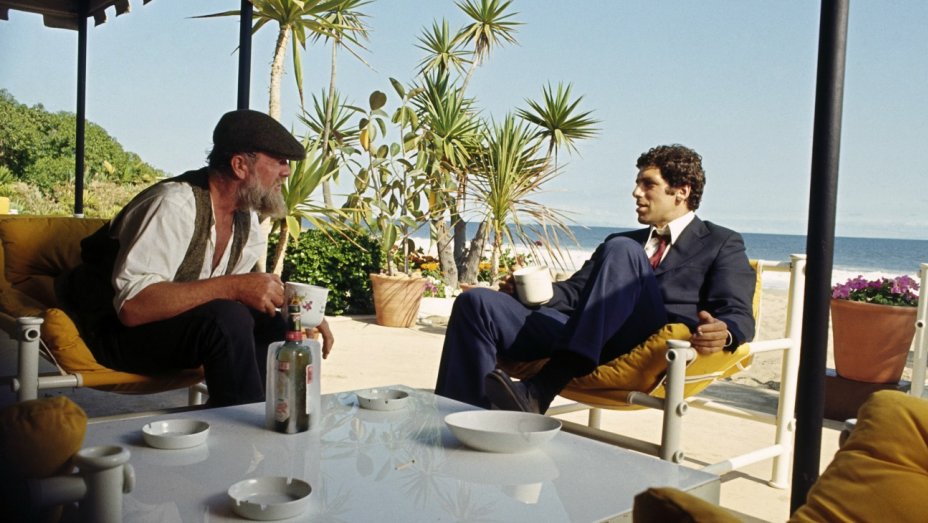

Marlowe receives a visit from his best friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) at three o’clock in the morning. Lennox has apparently had a bad fight with his wife Sylvia and wants to get out of town until things cool down. He asks Marlowe for a ride to Mexico and the private investigator obliges him. When Marlowe returns to Los Angeles, the police show up. They inform him that Sylvia Lennox has been found dead and that they suspect Terry. However, Marlowe does not believe Terry killed his wife. After spending a few days in police custody for refusing to cooperate, Marlowe begins his own investigation and finds himself entangled in a labyrinthine murder mystery. While attempting to prove his friend’s innocence, Marlowe encounters an array of unsavory characters, including a washed-up, alcoholic romance novelist, (Sterling Hayden), his rich, seductive, much-younger wife (Nina van Pallandt), an avaricious, drug-pushing quack psychiatrist (Henry Gibson), and a sadistic Jewish gangster (Mark Rydell) to whom Lennox owes money.

With its elaborate, gliding zooms and graceful tracking shots, The Long Goodbye exemplifies Altman’s remarkably fluid directorial style. Altman subverts the brisk, relentless pacing typical of many private eye films, allowing the streamlined narrative to unfold leisurely as a series of mostly comic set-pieces.

Altman made his intentions clear when the film was released: “Chandler used Marlowe to comment on his own time, so I thought it would be an engaging exercise to use him to comment on our present age.” A shaggy-dog story of a baffled gumshoe from 1953 cast adrift in the world of 1973, The Long Goodbye presents a piercing, formally innovative critique of film noir mythology, while satirizing the narcissism, decadence, and moral bankruptcy that pervaded American life after the decline of the counterculture.

Marlowe appears entirely out of touch with reality in that he maintains an unwavering commitment to his sleazy, so-called “friend,” despite intimidation from the police and Lennox’s criminal associates. He also allows himself to be deceived and used by a femme fatale who charms him with a candlelit dinner for two. Even the blissed-out women practicing nude yoga next door seem aware of his existence only when they want a favor from him. Rahul Hamid insightfully comments, “In Chandler’s novel, Marlowe’s superior morality is able to vanquish the fallen and corrupt noir world. Altman recasts Marlowe’s loyalty as irrelevant and naive in the modern world and changes the ending of the film to reflect this: Marlowe’s reassuring values, like the glamour of classic Hollywood, are revealed to be illusory and out of date.”

In The Long Goodbye, the visual conventions of the hard-boiled detective genre are radically altered. As opposed to the chiaroscuro lighting typical of film noir, Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond employ a technique called flashing, which involves partially exposing the negatives to light before they are developed. Hence the film has a distinctively hazy, washed-out look that simultaneously reinforces Marlowe’s lack of clarity and evokes the sense of a fading cinematic past. Critic Rogert Ebert, in his 2006 review of the film, also points out that “Most of the shots are filmed through foregrounds that obscure: Panes of glass, trees and shrubbery, architectural details, all clouding Marlowe’s view (and ours).” While Altman consistently defies viewer expectations and casts an analytical eye on the well-worn traditions of the American movie industry, The Long Goodbye nevertheless reveals a reverence for the history of film.

The director incorporates multiple references to classic Hollywood filmmaking: the security guard at the Malibu Colony does impressions of Barbara Stanwyck, James Stewart, Cary Grant, and Walter Brennan; Marlowe smears fingerprint ink over his face at the police station, recalling Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer; and the last scene of the film suggests the famous long take that concludes Carol Reed’s The Third Man.

At once an elegiac tribute to Hollywood, a brilliant exercise in genre deconstruction, an endlessly entertaining cinematic experience, and a bittersweet meditation on the shimmering instability of manufactured images, The Long Goodbye may be appreciated on multiple levels. In a 2007 article for the International Herald Tribune titled “Revisiting Altman’s The Long Goodbye,” Terrence Rafferty observes, “It’s a film about transience, about the awful fragility of the things we want to think are built to last: friendships, marriages, faiths of all kinds – including the faith that pop culture can sometimes makes us feel in powerful fantasy figures like Marlowe and his jaunty, street-smart, superbly incorruptible ilk.”