Attend: Program Notes

Attend: Program Notes

The Player | Robert Altman | US | 1992 | 124 minutes

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, March 4, 6:30pm»

Jason Fuhrman’s program notes for the Cinesthesia screening of The Player on Thursday night remind us that Robert Altman’s attitude about Hollywood was always complex and ambivalent.

“To play it safe is not to play.” — Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s multilayered movie about movies, The Player (1992), operates as both a subversive, meta-cinematic murder mystery and a funhouse mirror of the American film industry. Altman exposes the emptiness beneath Hollywood’s thick veneer of glamour and artifice, even as he plays with its clichés and customs. With its circular framework, endless in-jokes, allusive density, and star-studded lineup of cameo appearances, The Player contains something for just about everybody.

When Robert Altman died in 2006 at the age of 81, many critics regarded him as one of the most adventurous and influential American filmmakers of the late 20th century. Notable for their interwoven storylines, huge casts, overlapping dialogue, and open-ended narratives, Altman’s greatest films impart a lifelong fascination with human behavior, while breathing new life into the art of cinema.

An uncompromising artist who held to his eclectic vision in the face of commercial pressures, Altman evinced a skeptical disdain for the staid conventions of mainstream cinema. The combination of persistent experimentation, staunch criticism of America, and his interest in ideas rather than plot made him a provocative figure to the movie establishment.

Nevertheless, Altman always maintained a diplomatic outlook on the studio system. “I don’t have any perception of myself as being either in or out of Hollywood,” he once said. “I’m not, as people have said, ‘a maverick’ or someone who went off into exile. To me, Hollywood is a state of mind. I’m in Hollywood, I work in the business, in the system, but I’m also out of it.”

Following a series of commercial failures (Popeye, 1980; O.C. and Stiggs, 1985) and idiosyncratic passion projects (including Secret Honor, 1983; Fool for Love, 1985; Vincent and Theo, 1990), Altman was out of the Hollywood game. Anything but producer David Brown’s first choice to direct The Player, he came to the film only after several big-name directors, reputedly including Sidney Lumet and Walter Hill, passed on it.

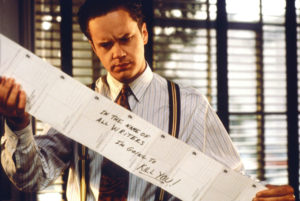

Based on a novel by Michael Tolkin (who adapted the screenplay himself), The Player follows the fortunes of Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins), a slick, manipulative and amoral Hollywood studio executive. After receiving anonymous poison-pen postcards from a screenwriter whom he has apparently neglected, Griffin finds himself entangled in a bizarre situation that increasingly comes to resemble the hackneyed crime melodramas his studio churns out. It’s Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. meets Jacques Tati’s PlayTime. Or Altman’s Nashville meets Fellini’s 8½.

Tolkin’s original crime novel is a well-written, if fairly straightforward, psychological thriller about a man approaching a breakdown under the strain of receiving anonymous, murderously threatening postcards. The film retains his basic plot, but Altman transformed the book into a funnier, brutally honest and convincing satire about the most egregious excesses of Los Angeles’ dream factory.

Far from a scathing indictment of Hollywood, The Player embraces a complex and ambivalent attitude toward the industry. In a 1992 interview with Geoff Andrew from Time Out magazine, Altman clarifies his creative intentions:

I made the film, not to take revenge on or chastise Hollywood, nor to become the manipulator in a town that likes to manipulate. True, Hollywood is a place I know a lot about, so Michael’s script was an opportunity to show a lot of the truth—which is what art is. My real motive in doing it was artistic; I just saw a chance to make something that was interesting, especially in terms of its structure, which is something most people don’t discuss. If you could draw a graph of how the film works, you’d see it has a very unusual structure—though I didn’t know if that would work until I’d finished the film.

A film-within-a-film (that also shows excerpts from two films being made within it), opens on a painting of a movie lot (the Charles Bragg lithograph, “The Screen Goddess”), in front of which a clapboard snaps shut to the sound of Altman’s own off-screen voice yelling, “Quiet on the set. Action!” While a studio security chief (played by Fred Ward) enthusiastically praises the opening of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958), the film proceeds with an impressive, eight-minute continuous shot that parodies long takes. Altman’s camera careens around the exteriors of the studio lot, observing and eavesdropping on various characters, even peeping through windows at hilarious improvised pitch sessions in progress. This explicitly cinematic introductory sequence sets the overall tone for The Player.

As The Player fluctuates between noir thriller, insider comedy, trenchant satire, and self-reflexive commentary, certain scenes deliberately emulate generic film styles, in terms of lighting and look. Throughout the film, Altman incorporates traditional, over-the-top music cues and cheap scare tactics, as well as all the requisite elements of a successful Hollywood product: suspense, laughter, violence, hope, heart, nudity, sex, and even a happy ending. At the same time, he defies audience expectations again and again, flaunting movie conventions only to then nonchalantly undermine them. For instance, a woman indeed takes her clothes off, but this is neither who nor when one would necessarily expect.

As The Player fluctuates between noir thriller, insider comedy, trenchant satire, and self-reflexive commentary, certain scenes deliberately emulate generic film styles, in terms of lighting and look. Throughout the film, Altman incorporates traditional, over-the-top music cues and cheap scare tactics, as well as all the requisite elements of a successful Hollywood product: suspense, laughter, violence, hope, heart, nudity, sex, and even a happy ending. At the same time, he defies audience expectations again and again, flaunting movie conventions only to then nonchalantly undermine them. For instance, a woman indeed takes her clothes off, but this is neither who nor when one would necessarily expect.

Altman inserts multiple visual puns that comment on the narrative and also evoke film history, such as panning to a portrait of Alfred Hitchcock and to framed posters for movies like They Made Me a Criminal (1939), Highly Dangerous (1950), The Hollywood Story (1951), and Joseph Losey’s second-rate 1951 remake of Fritz Lang’s 1931 classic M. From start to finish, Altman continually reminds us that we are watching a movie, that this a movie about movies, and eventually it becomes a movie about its own making.

The Player moves further away from reality until it ends by coiling back upon itself. As Altman states in a 1992 interview from Film Comment, “what we are saying is that the movie you saw is the movie you are about to see; the movie you saw is the movie we’re going to make.”

The ultimate irony of course is that The Player was a surprise art-house hit and Hollywood studio people tended to love it. In May 1992, Altman brought The Player to the 45th Cannes International Film Festival, where he won the Best Director award and Tim Robbins won the Best Actor award for his performance. As a result of the film’s success, a project that Altman had been dreaming about for years finally came to fruition. A dazzling, kaleidoscopic panorama of urban alienation adapted from nine short stories and a poem by Raymond Carver, Short Cuts (1993) elevated the auteur to an all-time personal peak. The one-two punch of these films thrust him back into the spotlight, and he remained prolific in his output until the end of his life.

Twenty-five years after Altman made a comeback with The Player, his artistic spirit exerts a vital influence on both art-house cinema and the commercial mainstream, now more than ever.