Attend: Program Notes

The Virgin Suicides | Sofia Coppola | United States | 1999 | 97 min.

Cinesthesia, Madison Public Library Central Branch, Thursday, June 6, 6:30 p.m.»

A poetic, timeless, and entrancing meditation on teenage angst and inexpressible loss, Sofia Coppola’s confident debut feature, The Virgin Suicides, dresses up 1970s upper-middle-class suburban existential horror with lush visuals, pitch-perfect period detail, and plenty of verve.

The awful thing about life is this: everyone has their reasons.

Jean Renoir, The Rules of the Game (1939)

An adaptation of the acclaimed 1993 novel by Jeffrey Eugenides, The Virgin Suicides plunges viewers into the murky emotional depths of female adolescence, while fluidly evoking upper-middle-class suburban life in the late 1970s. Sofia Coppola’s luminous, intoxicating, and assured debut feature acutely observes the interior worlds of five preternaturally beautiful sisters, ranging in age from 13 to 17, who inexplicably take their own lives. Raised on the outskirts of Detroit by their strict, domineering Catholic parents, the Lisbon sisters lead an increasingly cloistered existence and become the objects of erotic fascination for a group of oblivious teenage boys. The tragic tale unfolds through the wistful voice-over narration of one of the boys (played by actor Giovanni Ribisi) who, now approaching middle age, recalls their experiences with the girls and attempts in vain to make sense of their lives and deaths.

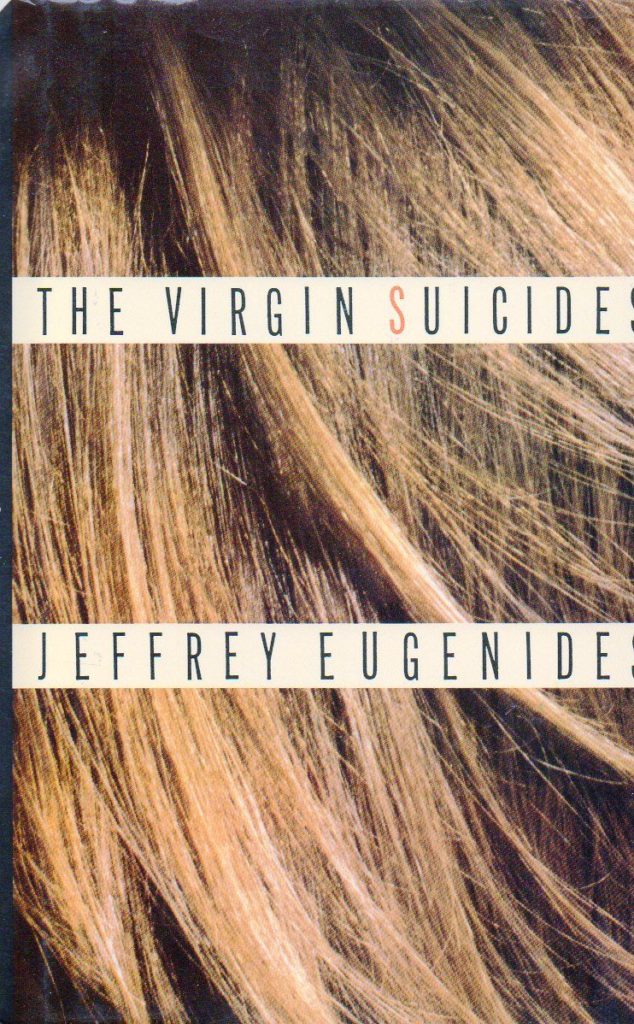

Coppola came across The Virgin Suicides in her mid-20s when Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth reportedly gave her a copy of Eugenides’s book. The director remembers liking the cover, “a close-up of blond hair unspooling on the ground.” Her adaptation of The Virgin Suicides was an “experiment” in screenwriting, a labor of love motivated by her adoration of the novel. “It felt like Jeffrey Eugenides, the writer, really understood the experience of being a teenager: the longing, the melancholy, the mystery between boys and girls. I loved how the boys were so confused by the girls, and I really connected with all that lazing around in your bedroom. I didn’t feel like I saw that very much in films, not in a way I could relate to.”

After completing the script, Coppola was dismayed to learn that another company owned the rights to the novel and was already producing an adaptation of their own. However, they were unsatisfied with the “really dark” draft they had originally commissioned, and eventually met with Coppola, who pitched her version as having “a lighter touch.” Hence, Eugenides’s novel led to Coppola’s career as a filmmaker.

“With a book like this, no one should really play the characters,” Eugenides once mused when asked about the adaptation, “because the girls are seen at such a distance. They’re created by the intention of the observer, and there are so many points of view that they don’t really exist as an exact entity . . . I tried to think of the girls as a shape-shifting entity with many different heads. Like a hydra, but not monstrous. A nice hydra.” Moreover, Coppola has said that, for her, The Virgin Suicides is about “how deeply people can affect you, and how little images can get the biggest importance, and never go away.”

Coppola beguiles us with ethereal, dreamlike images as she offers a seamless succession of shimmering surfaces that mask the deep emptiness and creeping inevitability at the heart of The Virgin Suicides. Rather than attempting to explain the behavior of the Lisbon sisters, she focuses mostly on the boys’ gaze by visualizing their desires, speculations, and idle reveries. At the same time, Coppola peers into the sisters’ harsh reality, revealing private aspects of their day-to-day lives that the boys cannot see. She portrays them as individual young women and insists that we look beyond the boys’ limited perspective.

In an essay on the film, novelist Megan Abbott writes, “From the start . . . we see that the standard narratives, the endless cultural fantasies about teenage girls, are going to be played with, refused, subverted—a point driven home in the shot just after the opening title, in which the screen fills with Lux’s image, superimposed, godlike, across the sky as she gazes into the camera (and us) and winks.”

Although the presence of death permeates The Virgin Suicides at the outset—thirteen-year-old Cecilia slits her wrists and a diseased tree has been marked to be sawn down by the city—Coppola punctuates her movie with moments of black humor. She exhibits an elegant filmmaking style that counterbalances the grim storyline, while seducing us into the hazy, poisonous, hermetic world of the Lisbon family. The audience already knows that the film will not have a happy ending, but The Virgin Suicides casts a spell.

Like the unwary teenage boys who find themselves smitten and bewildered by the girls’ mystery, and who as men try to extract some sort of meaning from the tragedy, we too are lost in our efforts to either understand their actions or decipher an elusive femininity that seems forever just beyond our reach. In the end, the film leaves us with little more than a collection of haunting memories that defy elucidation.

“When I was growing up, movies for teens were always lowbrow and not well crafted, and it was hard to relate to them,” Coppola said in a recent interview. “There wasn’t much poetic filmmaking that spoke to me as a girl and a young woman, and also treated [us] with respect I felt that audience deserved.” She recalls that the now-defunct studio Paramount Classics, which distributed the movie, was afraid it would encourage teen suicides and gave it a small release. Nonetheless, The Virgin Suicides caught on as a cult classic, spurred by its unique look, its iconic soundtrack (mostly by the French electronic duo AIR), and the rising stardom of Kirsten Dunst, who portrays the enigmatic, wayward fourteen-year-old Lux Lisbon.

Even though Coppola went on to pursue an illustrious career in American independent cinema, The Virgin Suicides arguably remains her finest achievement, a singular combination of sound and vision, a poignant blend of pathos and comedy, and an art-house teen movie touchstone. Twenty years since its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, Coppola’s masterpiece continues to resonate with audiences of multiple generations.

Discussing her creation with The Guardian in 2018, she said that “a couple of years ago, a bunch of teenage girls told me how much they loved The Virgin Suicides. I thought: ‘How do they even know about that? They weren’t even born.’ Through the internet, it’s had a second life. It’s nice to know that it still speaks to some young women.” On April 24, 2018, a restored version of the film was released on DVD and Blu-ray via the Criterion Collection, to the delight of cinephiles and Coppola alike.

The director-approved special edition of The Virgin Suicides includes a 4K digital transfer supervised by cinematographer Ed Lachman, new interviews with the cast and crew, a making-of documentary filmed by Coppola’s mother, Eleanor, and Lick the Star, a 1998 student short film by Coppola. In his review of the Blu-ray treatment, Niles Schwartz writes, “The transfer practically allows the colors to talk in a stunning multivaried [sic] palette, the spectrum of plentiful hues popping with gorgeous distinction, the fleshier warm colors in a kind of showdown with the smothering suffocation of blue and mossy green.”