Discuss: Jake’s Take on the 2016 Wisconsin Film Festival at the Halfway Mark

Jake Smith shares brief thoughts on the films he has seen so far at the 2016 Wisconsin Film Festival.

My festival experience thus far has been unusual. Unlike previous years, where I have done a fairly good job of mixing it up in terms of the types of films I’ve taken in, this time around I have focused far more exclusively on the restorations and revivals, particularly the “One and Done” screenings. My post here, then, ends up echoing Jim Healy’s sentiments in the introduction he gave to The Well, taking the form of a kind of retroactive advocacy. My writing below is mostly composed of reactions to the films; plot summaries can be found by clicking on the titles of each program.

As always, before I get started here, allow me to thank all of you who help bring the Festival to us. Be you on the front lines or behind the scenes, it’s hard work. Thank you for it.

With that, here we go:

The Well

The Well

Leo Popkin & Russell Rouse | USA | 1951| 86 min

In Jim Healy’s introduction to this film, he talked about the screening itself as an act of advocacy. It was not only about exposing people to the film; it was also about getting people talking about it, because it’s a film that’s in need of saving. From the quality of the digital print that we saw, it’s certainly in need of restoration. But is this one-off worth the effort to do so? On no uncertain terms, yes. On a stylistic level, it’s a fascinating exercise in how information is conveyed both to audience and characters alike. There is also a very definite and very effective editorial rhythm on display, particularly in the montage sequences, that is as compelling as the film’s subject matter. On a narrative level, there are moments in the story that after these many years will still stop your breath or drop your jaw. Harry Morgan, in particular, was flat-out amazing. It carries some of the hysterically quick plotting that many social problem films of the time seem to have, but the urgency of the missing child and the racial tensions that so quickly rise to the surface remain emotionally believable. My colleague James Kreul reviewed the film in greater depth here. I hope that whatever rights issues can be squared away soon and proper restoration work can begin. The Well is a film that needs saving, a film that needs seeing.

Nothing Lasts Forever

Tom Schiller | USA | 1984 | 82 min

Yep. That’s a bus on its way to the moon in that poster to the right. I would think that a movie with a poster image that absurd would be quite promising. After watching Nothing Lasts Forever, despite the excitement that comes with viewing something so rare, I find myself agreeing with my colleague Taylor Hanley (check out her review here). A little of Nothing Lasts Forever goes a long way. On the one hand, the film does quite well in generating a retro-futuristic atmosphere, and I found its eventual narrative symmetry both unexpected and bizarrely rewarding. On the other, I felt like the comedy in the film was more in the concept than in the execution. That said, “Schiller’s Reel,” the collection of shorts that preceded the feature, was nothing short of brilliant, and not just because that collection included the melancholy joy of seeing John Belushi dance atop the snowy graves of his SNL co-stars. The number of great ideas on display in such a few short films was truly staggering. Seeing the shorts before the feature probably impacted my opinion of the feature far more than they should have. I tend to prize narrative economy, so when I compared the number of brilliant ideas in such a short space of time to the feature’s fewer-but-equally-brilliant ideas stretched to their limit across 82 minutes, I suppose I was bound to enjoy the shorts more. Still, it’s great to have the opportunity to see both the shorts and the feature, particularly with a crowd—something I find increasingly crucial for comedies. I wish I had had time to stick around for the Q&A, as I’m sure Tom Schiller had some great stories. As with any festival, though, sacrifices must be made. In my case, I had to get to my next film.

Yep. That’s a bus on its way to the moon in that poster to the right. I would think that a movie with a poster image that absurd would be quite promising. After watching Nothing Lasts Forever, despite the excitement that comes with viewing something so rare, I find myself agreeing with my colleague Taylor Hanley (check out her review here). A little of Nothing Lasts Forever goes a long way. On the one hand, the film does quite well in generating a retro-futuristic atmosphere, and I found its eventual narrative symmetry both unexpected and bizarrely rewarding. On the other, I felt like the comedy in the film was more in the concept than in the execution. That said, “Schiller’s Reel,” the collection of shorts that preceded the feature, was nothing short of brilliant, and not just because that collection included the melancholy joy of seeing John Belushi dance atop the snowy graves of his SNL co-stars. The number of great ideas on display in such a few short films was truly staggering. Seeing the shorts before the feature probably impacted my opinion of the feature far more than they should have. I tend to prize narrative economy, so when I compared the number of brilliant ideas in such a short space of time to the feature’s fewer-but-equally-brilliant ideas stretched to their limit across 82 minutes, I suppose I was bound to enjoy the shorts more. Still, it’s great to have the opportunity to see both the shorts and the feature, particularly with a crowd—something I find increasingly crucial for comedies. I wish I had had time to stick around for the Q&A, as I’m sure Tom Schiller had some great stories. As with any festival, though, sacrifices must be made. In my case, I had to get to my next film.

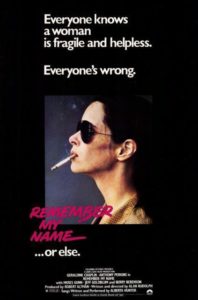

Remember My Name

Remember My Name

Alan Rudolph | USA | 1978 | 96 min

Of the films I haven’t seen in this festival, this one is far and away my favorite. No one does jazz, neon, and foibles like Alan Rudolph. Like Nothing Lasts Forever, this is a film where everything changes for its characters, and yet it still ends where it begins. As Rudolph films often are, Remember My Name is alternately harrowing and humorous in its intensely watchable depiction of some intensely flawed human beings. The film is packed with distinctive little touches that make already memorable performances even more so (my favorite being Geraldine Chaplin’s penchant for putting out her cigarettes with her thumb). If I have a complaint about this movie at all, it’s that there wasn’t nearly enough Tim Thomerson. Back to the theme of retroactive advocacy, it’s a genuine shame that this film is so hard to see. Aside from the film’s many merits, at multiple points I couldn’t help but think how interesting it would be to put this film side-by-side with another 1978 picture about an ex-con rejoining society: Straight Time. Straight Time may be better known, but Remember My Name may be the better film.

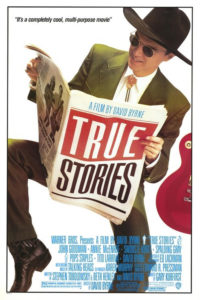

True Stories

David Byrne | USA | 1986 | 115 min

David Byrne | USA | 1986 | 115 min

In the spirit of full disclosure, I am a native Texan, so I may view this film a little differently than most of those in the audience. After all, I have driven down many of the same roads on which you see David Byrne’s crazily-yet-impeccably dressed narrator driving, and I have memories of being in or around some of the film’s locations. Thus, on one level, I take a very personal pleasure out of this film. I get to see a Texas sky captured like it should be, with grandeur and a dash of oddity waiting below. On another level, I was struck by how sophisticated the satire is, and how well it holds up. It is simultaneously dated and prescient, making it play as inexplicably timeless. It is also a film that manages to satirize without biting, to ridicule without denigrating. The film is bankrupt of snark, which is a quality all too rare in contemporary satire. I have always enjoyed this film, but after seeing it on 35mm, I am reminded that it is truly one of the best films of the 1980s, and certainly one of the most distinctive. While Remember My Name may be my favorite of those films I hadn’t seen previously, seeing True Stories on the big screen, on film, has been my greatest joy of the festival thus far. I feel lucky I got to see the film this way.

Tim Horton’s Head Meets the Killer: Wisconsin’s Own Experimental Shorts

During the Q&A session for this program, director Bill Bedford (who made two of the shorts in the program) turned the spotlight on the audience and asked it a question: why do you think the programmers grouped these films together? It took a minute for people to answer, but it generated some good discussion. Ultimately, that’s why I feel the programmers grouped these films together: to generate a discussion within your own mind. The way that ideas ricochet across different films in experimental programs is but one of the intellectual and emotional joys that they provide. Programs like are often a mixed bag. This one was no different, though as Bedford mentioned (and I agree), all of the directors here brought a consummate attention to their craft. None of them seemed like projects; regardless of their formats, they were all films. The two that stood out for me were Scott Stark’s Traces/Legacy—whose jarring abstract patterns proved fascinating in their intersections of the audio and the visual—and John Powers’ The House You Were Born In (pictured here), whose overlapping narration and poetic visual command of the frame combine to form an extraordinarily evocative exploration of memory and the powerful concept of home. The one surprise was the Guy Maddin film, Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, and not in a good way. All of the work that preceded it felt more vibrant than Maddin’s piece, which was more of an exercise than an enjoyment.

During the Q&A session for this program, director Bill Bedford (who made two of the shorts in the program) turned the spotlight on the audience and asked it a question: why do you think the programmers grouped these films together? It took a minute for people to answer, but it generated some good discussion. Ultimately, that’s why I feel the programmers grouped these films together: to generate a discussion within your own mind. The way that ideas ricochet across different films in experimental programs is but one of the intellectual and emotional joys that they provide. Programs like are often a mixed bag. This one was no different, though as Bedford mentioned (and I agree), all of the directors here brought a consummate attention to their craft. None of them seemed like projects; regardless of their formats, they were all films. The two that stood out for me were Scott Stark’s Traces/Legacy—whose jarring abstract patterns proved fascinating in their intersections of the audio and the visual—and John Powers’ The House You Were Born In (pictured here), whose overlapping narration and poetic visual command of the frame combine to form an extraordinarily evocative exploration of memory and the powerful concept of home. The one surprise was the Guy Maddin film, Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, and not in a good way. All of the work that preceded it felt more vibrant than Maddin’s piece, which was more of an exercise than an enjoyment.

I’ll have more on the second half of my festival experience in a few days. In the meantime, feel free to share your thoughts on these films or any of the others that you’ve seen in the comments below!