Hitchcock Week: Part One of Five

Hitchcock Week: Part One of Five

This week the Madison Film Forum will present reflections on the next five films in the UW Cinematheque’s Hitchcock Masterworks series. These are not intended as reviews for readers who have not seen the films. We hope they will serve as the start of a conversation with those who have seen the films and will be revisiting them at the UW Cinemathque series, or through the streaming resources linked at the end of the entries. First up, our friend and colleague Jay Antani from CinemaWriter.com offers his reflections on Rope (1948), which will play at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, March 2 at 2:00 pm.

Appreciating Rope (1948)

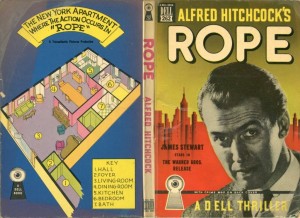

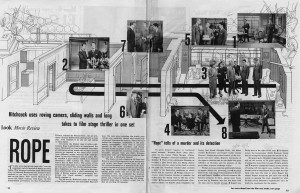

Of all the dazzlers that the Master made during the Hollywood phase of his career, Rope (1948) is one of his more underrated. It doesn’t boast huge names in the lead (though Jimmy Stewart has a supporting, albeit crucial, role) like Notorious (1946), elegant locales like To Catch a Thief (1955) nor the exciting espionage of North by Northwest (1959), with its booming Bernard Herrmann score. Rope, in fact, has no score, apart from what we hear during the opening and closing credits. It’s a small movie that never leaves its one setting—an upscale New York apartment—but Hitchcock uses that close, contained space to amplify the characters’ (and our) sense of entrapment over its 80 real-time, claustrophobic minutes. Rope unfolds as a series of 10-minute takes, cut together as seamlessly as possible to give the impression of one continuous shot. For Hitchcock, it was a stimulating exercise for distracting himself from the tediousness of shooting a movie (Hitch often had entire scenes already cut and crafted in his mind so that the act of actually shooting the films felt like a chore). But Rope’s technical virtuosity isn’t just gimmick: The roving eye of the camera becomes a character in itself as it follows two friends, Brandon (John Dall) and Phillip (Farley Granger) from the point of murdering a classmate and hiding his body inside a trunk on through their setting up a banquet served atop said trunk and inviting their unsuspecting, high-society friends over for the evening.  The camera is both a voyeur witnessing the murder, and a prosecutor searching the characters’ faces for signs of guilt, panic and suspicion as the evening wears on. What’s so much fun in watching Rope is how Hitch blocks the action: Everything has to be arranged and positioned so that the camera can most easily view it without cutting in for close-ups or reverse angles. The camera itself has limited physical ability: It can track the width and length of the space, but that’s it. And without editing—the suspense director’s most vital tool—Hitchcock had to shift his strategy for conveying big reveals. In Rope, mise-en-scène became his best and only friend. All this leads to a delightful kind of cinematic staginess. The action is blocked to allow the camera to capture key facial expressions and gestures as characters run through their dialogue and move through the space. A combination of blocking and timing also lets the camera pick up key story beats; look fast as a gleeful Brandon drops the incriminating length of rope into a kitchen drawer exactly when the kitchen door swings open for the camera to peer through.

The camera is both a voyeur witnessing the murder, and a prosecutor searching the characters’ faces for signs of guilt, panic and suspicion as the evening wears on. What’s so much fun in watching Rope is how Hitch blocks the action: Everything has to be arranged and positioned so that the camera can most easily view it without cutting in for close-ups or reverse angles. The camera itself has limited physical ability: It can track the width and length of the space, but that’s it. And without editing—the suspense director’s most vital tool—Hitchcock had to shift his strategy for conveying big reveals. In Rope, mise-en-scène became his best and only friend. All this leads to a delightful kind of cinematic staginess. The action is blocked to allow the camera to capture key facial expressions and gestures as characters run through their dialogue and move through the space. A combination of blocking and timing also lets the camera pick up key story beats; look fast as a gleeful Brandon drops the incriminating length of rope into a kitchen drawer exactly when the kitchen door swings open for the camera to peer through.

The technical demands of the film create a palpable tension in the performances too. I don’t mean in the drama itself, but in the ways the actors have to adapt to the film’s shooting style. Dall, Granger and company try mightily to exude a naturalism in how they move or behave, but the fact that they have to stand around in awkward, mannered poses—sometimes facing the camera, with their backs to each other—is what makes Rope so endearing. Yes, Rope is an endearing movie: That sense of the performers fighting the form gives the film a kind of meta-tension that endears the performers—and the whole project—to us that much more. There’s definitely tension within the story (will the guests discover the dead body?), but it’s that larger one—the tension between actor and camera—that’s even more of a pleasure to follow. And Hitch doesn’t stop there. Because it’s told in real time, we see the play of light outside the huge apartment windows as evening turns to night. It’s a whole other dimension for appreciating Rope: Take a look at how the orange and purple tints outside the window mellow and bloom before the sky darkens and the neon lights in the city backdrop come on and the billboards start to blink. This may be a one-set movie, but there’s that sense of a larger world thanks to Hitch and cinematographers William V. Skall and Joseph Valentine’s mastery of lighting. And as the outside world transforms, the filmmakers alter the interior lighting in sync with it; that dance of “exterior” and “interior” lighting is beautiful and just as captivating to me as the more tension-fraught dance of the performers. Rope is a lot like Dial M for Murder (1954) in that the technical bravura of the films (Dial M is hyped as Hitchcock’s attempt at 3D) tends to overshadow how good the movies underneath really are. I think Rope does a better job than Dial M in integrating its peculiar style (i.e., its one-take prosecutorial camera) into the rising tide of its drama. But what’s interesting about both films is how much you want the villains to get away with their crimes. Ray Milland’s Tony Wendice in Dial M is one smooth operator and a more sympathetic character than Rope’s Brandon, who’s an obvious, high-society prick to Milland’s more genteel cuckold. Nevertheless, for his sheer, sinister intelligence, Brandon is the kind of psychopath who’d have half a chance at success—if only his yammering milquetoast of a sidekick could keep it together.

In addition to the March 2 screening at the UW Cinematheque Hitchcock Masterworks series, Rope is also available to rent from Amazon Instant Video: