Hitchcock Week: Part Five of Five

Hitchcock Week: Part Five of Five

This past week the Madison Film Forum has presented reflections on the next five films in the UW Cinematheque’s Hitchcock Masterworks series. These are not intended as reviews for readers who have not seen the films. We hope they will serve as the start of a conversation with those who have seen the films and will be revisiting them at the UW Cinematheque series, or through the streaming resources linked at the end of the entries.

In the final installment, James Kreul realizes that he hadn’t actually seen Strangers on a Train, which will play at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, March 9 at 2:00 pm.

One Image from Strangers on a Train (1951)

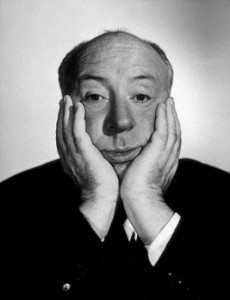

How is it that I had never actually seen Strangers on a Train until we divided up the next five Hitchcock films at the UW Cinematheque series to write about at Madison Film Forum? And why did one image, the image on the right, stick out for me when I finally did watch it this week?

Certainly I should have seen Strangers before now. In high school didn’t I used to comb through the TV listings to see what movies were coming up so that I could record them based on their Leonard Maltin guide reviews? Didn’t I go to the library to devour Halliwell’s Filmgoer’s Companion, and eventually buy my own copy, so that I could make lists of films by directors I should know about? Didn’t I take Bill Keys’s Film Study class at West High School, which truly introduced me to Hitchcock via Psycho (1960)? Didn’t I then read all of Truffaut’s book-length interview, Hitchcock (a.k.a. Hitchcock/Truffaut), and read about all the films, even the ones that were not available on video? Didn’t I know, of course, that Throw Momma from the Train (1987) was a comic reworking of the same premise? How could I have done and known all of these things but not have seen Strangers on a Train?

It turns out, upon further review, that I have a Hitchcock blind spot: the early 1950s. I hadn’t seen Under Capricorn (okay, that’s 1949), Stage Fright (1950), Strangers on a Train (1951), I Confess (1953), The Trouble with Harry (1955) and The Wrong Man (1956, okay, those last two are mid-1950s). None of those films, even Strangers, receives the kind of attention that is showered on the other classics of the 1950s, especially Vertigo (1958) which recently knocked Citizen Kane (1941) out of the top spot in the Sight and Sound list of the 50 Greatest Films of All Time.

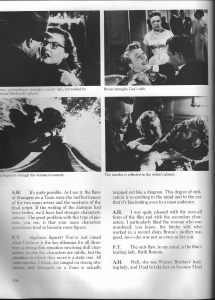

So why did I feel like I had seen Strangers on a Train? I blame Truffaut. If you had asked me what object I associated with Strangers, I would not have said “train,” or “lighter,” I would have said “glasses.” After all these years, I still had the page from Hitchcock/Truffaut on the right in mind when I thought of Strangers. It explains the parallel between glasses worn by murder victim Miriam Haines (Kasey Rodgers) and glasses worn by young Barbara Morton (Patricia Hitchcock, Hitch’s daughter). If you click on the picture to look closer, you’ll see that the publishers accidentally switched around the captions. But despite that confusion, I remembered that Bruno (Robert Walker) recalls the earlier murder when he sees young Barbara while he is demonstrating how powerful his hands are around the neck of an elderly partygoer. This leads him to start strangling the woman, which in turn leads Ann Morton (Ruth Roman) to connect the dots between Bruno and the murder of Miriam, the wife of her fiancee-to-be, Guy Haines (Farley Granger). That page from Hitchcock/Truffaut served the same function for me that frame enlargements from Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964) has served for the many people who have discussed Empire without having seen it.

So why did I feel like I had seen Strangers on a Train? I blame Truffaut. If you had asked me what object I associated with Strangers, I would not have said “train,” or “lighter,” I would have said “glasses.” After all these years, I still had the page from Hitchcock/Truffaut on the right in mind when I thought of Strangers. It explains the parallel between glasses worn by murder victim Miriam Haines (Kasey Rodgers) and glasses worn by young Barbara Morton (Patricia Hitchcock, Hitch’s daughter). If you click on the picture to look closer, you’ll see that the publishers accidentally switched around the captions. But despite that confusion, I remembered that Bruno (Robert Walker) recalls the earlier murder when he sees young Barbara while he is demonstrating how powerful his hands are around the neck of an elderly partygoer. This leads him to start strangling the woman, which in turn leads Ann Morton (Ruth Roman) to connect the dots between Bruno and the murder of Miriam, the wife of her fiancee-to-be, Guy Haines (Farley Granger). That page from Hitchcock/Truffaut served the same function for me that frame enlargements from Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964) has served for the many people who have discussed Empire without having seen it.

Finally catching up with Strangers this week, the reflection of Bruno’s murder of Miriam in her fallen glasses makes an grand impression, but another stylistic flourish stood out for me. First we have to recall that Miriam’s glasses play against type (of the time), but young Barbara’s glasses fit into a common representation of the smart(-alec) young girl. So while it might have been surprising for the vamp (harsher words are used in the film) to wear glasses, it wasn’t unusual for the little sister to wear them. When Barbara first appears, she is contrasted with her older sister Ann, the female lead; we quickly learn to expect Barbara to say things that the adults are too subtle and mature to say. We expect Barbara to be a quirky minor character, not the catalyst for a turning point for Bruno.

But the first time Bruno sees Barbara at the tennis club, Hitchcock marks Bruno’s response with wonderful stylistic excess. It is classic shot-reverse shot, with a layer of subjective cues just in case we might not get the the idea that Barbara’s glasses remind Bruno of Miriam’s glasses.

We first get a close up of Bruno, whose face has turned from jovial to morose in the instant that he first lays eyes on Barbara. Barbara enters the conversation assuming that she is joining a jovial one. But then she shifts her gaze back to Bruno, and Patricia Hitchcock looks directly into the camera. The camera slowly dollies forward and tilts up slightly into Barbara’s face; her flirtatiousness shifts to discomfort as she tries to interpret Bruno’s shift in disposition.

This sets up one of those great cinematic moments where you’re excited both by the narrative developments as well as the stylistic touches of the director. Above I’ve described the dramatic conflict. But as a viewer one also wonders how far Hitchcock will go stylistically to punctuate this moment. What I’ve enjoyed most about the Hitchcock Week articles has been the opportunity to share the bliss one can experience when Hitchcock pulls off a stylistically audacious moment in an otherwise straight-forward sequence.

This sets up one of those great cinematic moments where you’re excited both by the narrative developments as well as the stylistic touches of the director. Above I’ve described the dramatic conflict. But as a viewer one also wonders how far Hitchcock will go stylistically to punctuate this moment. What I’ve enjoyed most about the Hitchcock Week articles has been the opportunity to share the bliss one can experience when Hitchcock pulls off a stylistically audacious moment in an otherwise straight-forward sequence.

As the camera approached Barbara, I asked myself, “Is Hitchcock going to do something with the glasses?” He first adds some sound cues that serve to flashback to the murder. Was that going to be enough? Or was he going to do something visually with the glasses that would echo the reflection of the murder itself. The camera’s getting closer, something’s going to have to happen when we get to a close-up. It can’t be an actual reflection of Bruno or the table, what good would that do? Will he do something akin to a Tex Avery gag in a cartoon or a Frank Tashlin gag where the man’s glasses crack when he sees a beautiful woman? Then, boom.

We get my favorite image in Strangers on a Train. Punctuated by the sound of Guy’s lighter, we see lighters superimposed in both lenses, as if they were reflections. There are many reasons this shouldn’t work, but it does work. Unlike an Avery or Tashlin moment, this is not supposed to be funny, instead it is creepy and menacing (with a touch of Hitch’s dark humor, of course). Unfortunately, the “kids today,” who see anything old as camp, will probably laugh at this moment at the UW Cinematheque screening—but shout them down for me if they do. Perhaps we shouldn’t be too hard on them, since they’ve been taught that similar excesses in style, like what we see in most of Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010), are supposed to be funny or just clever. But there was a time when such flourishes could be used for a range of functions and purposes, not just self-aware irony.

We get my favorite image in Strangers on a Train. Punctuated by the sound of Guy’s lighter, we see lighters superimposed in both lenses, as if they were reflections. There are many reasons this shouldn’t work, but it does work. Unlike an Avery or Tashlin moment, this is not supposed to be funny, instead it is creepy and menacing (with a touch of Hitch’s dark humor, of course). Unfortunately, the “kids today,” who see anything old as camp, will probably laugh at this moment at the UW Cinematheque screening—but shout them down for me if they do. Perhaps we shouldn’t be too hard on them, since they’ve been taught that similar excesses in style, like what we see in most of Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010), are supposed to be funny or just clever. But there was a time when such flourishes could be used for a range of functions and purposes, not just self-aware irony.

Another reason not to be too hard on “the kids” is that I’ve now discovered, thanks to Google Analytics, that they are far more likely to be reading the Madison Film Forum than anyone my age or older. So here’s hoping that some of them in the course of this past week have discovered a reason or two to catch one or more films in the UW Cinematheque Hitchcock series, The internet is their Halliwell’s guide, and some of them have probably watched the clip I discussed here online by the time you finish reading this.

In addition to the March 16 screening at the UW Cinematheque Hitchcock Masterworks series, Strangers on a Train is also available to rent from Amazon Instant Video and Vudu: