Hitchcock Week: Part Four of Five

Hitchcock Week: Part Four of Five

This week the Madison Film Forum will present reflections on the next five films in the UW Cinematheque’s Hitchcock Masterworks series. These are not intended as reviews for readers who have not seen the films. We hope they will serve as the start of a conversation with those who have seen the films and will be revisiting them at the UW Cinematheque series, or through the streaming resources linked at the end of the entries.

In today’s installment, regular contributor Jake Smith discusses Rear Window (1954), which will play at the Chazen Museum of Art on Sunday, March 16 at 2:00 pm.

Rear Window (1954)

Rear Window (1954)

Popularly acclaimed and critically revered, Rear Window is an essential cinematic experience. Like most of Hitchcock’s films, it has also been discussed, analyzed, and deconstructed by a great many critics and scholars. In light of that scrutiny, I would not make a claim to say anything spectacularly new about this masterpiece, but like my earlier post on Shadow of a Doubt, there are some specific moments that I will celebrate here.

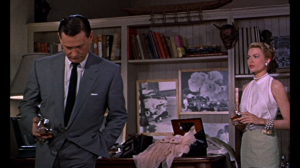

For one, as with most of Hitchcock’s oeuvre, humor goes hand-in-hand with suspense and fright. The script is one of the wittiest that Hitchcock ever put to screen, but one moment that always gets me is one not of verbal comedy but of physical comedy. It comes while Jeff (James Stewart) and Lisa (Grace Kelly) continue make their case to Detective Doyle (Wendell Corey) that neighbor Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) murdered his own wife.

Lisa provides brandy to everyone, and for a few moments the three of them relentlessly swirl the brandy around in their snifters. This kind of synchronized “business” (in the acting sense of the word) draws just the right amount of attention to itself, just enough to make it ceaselessly humorous without being ridiculous. It’s just another day in the apartment of L.B. Jeffries: three people just rolling their brandy around their glasses, chatting about murder.

In that same scene, though, we also see Hitchcock’s bravura staging and camera movement on display. Even though the characters in these shots are only taking a few steps across a typical apartment living room, they almost seem to gently glide through the frame in this scene. We start with Doyle in close-up, as he moves away from Jeff and Lisa, having made the point that he just doesn’t buy their case for Thorwald as murderer.

Then cut to Lisa, by no means dissuaded, who leaves Jeff’s side to further convince Doyle.

The camera holds here for a few seconds as she argues in Jeff’s favor. Then cut to Jeff, who rolls right between them to take center stage in the argument.

Hitchcock then repeats the pattern, but varies it in that Jeff is the first to follow Doyle, and Hitchcock doesn’t cut. Doyle walks over to the chair to sit down.

Jeff doesn’t give up, wheeling himself closer to Doyle to keep after him, and the camera moves in, excluding Lisa.

When she is brought back into the fray, by not cutting, Hitchcock allows Grace Kelly to make another of her many easy, graceful entrances, even though she’s doing something as ordinary as rejoining the conversation.

The inspiration provided by the constraints of the small space, the ever- shifting triangulation of the characters as Lisa and Jeff take turns on point making their case, the elegant command with which Hitchcock guides the viewer’s attention (to say nothing of the outstanding performances)—these thrill me every time I watch the film.

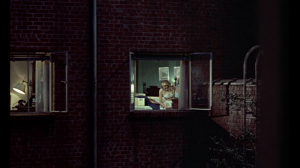

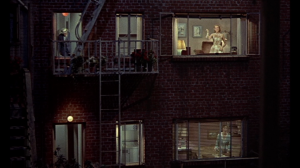

Speaking of Hitchcock’s command of the viewer’s attention, there is one last sequence that I would point out. The moment comes when Lisa has successfully broken into Thorwald’s apartment to find a key piece of evidence, which already provides a fair amount of suspense.

While she is there, Hitchcock cuts to the downstairs neighbor, whom it has been established is on the verge of committing suicide, shifting the focus of the suspense while adding to it.

Once we see the neighbor respond to the beautiful music she hears from an apartment across the way, the joy we feel is immediately overcome by a burst of irrefutable tension when Lisa and the neighbor are then in the same frame…

…for we then see none other than Thorwald making his way back to the front door of his apartment.

The way Hitchcock’s framing guides the viewer’s eye is at once exacting and seemingly effortless, and much like Jeff, the viewer goes through a succession of decisions as to where else to look once Hitchcock has initially directed that eye.

The humor and the suspense of Hitchcock’s work are two qualities that are undeniably endearing and enduring. We all have our favorite moments, and these are but a few of mine. Among his work, Rear Window is certainly one of the most universally crowd-pleasing. Don’t miss your chance to see it on the big screen, or rather chances, as it will be screening twice in the Madison area in March. Sundance will be projecting it digitally on March 5, but if you want to see Hitchcock the way it’s meant to be played, wait until March 16 and catch it in 35mm at the Chazen Art Museum.

In addition to the March 16 screening at the UW Cinematheque Hitchcock Masterworks series, Rear Window is also available to rent from Amazon Instant Video and Vudu: