Missed Madison Film Festival

HyperNormalization | Adam Curtis | UK | 2016 | 166 minutes

Unofficial YouTube Channels: Here and Here

Even if you dismiss the style and rhetorical techniques of documentarian Adam Curtis, his HyperNormalization does shed light on many issues of the day, and delivers several sublime, transcendent reveals.

Here’s another slight “cheat” on the premise of the Missed Madison Film Festival. Adam Curtis’s 2016 documentary for BBC iPlayer, HyperNormalization, was never going to play in Madison theaters. Because of Curtis’s extensive use of BBC archives and other copyrighted material, he simply would never get official licensing for a legitimate release, theatrical or otherwise, of most of his films outside of the BBC. Officially, the only way to watch HyperNormalization is on BBC iPlayer, which can only be (officially) accessed by IP addresses in the United Kingdom.

But as we all know, you can’t contain ones and zeroes. There are many sources across the internet for access to the film beyond the YouTube links above.

Curtis is an incredibly talented, entertaining, and provocative documentary filmmaker. His use of archival news footage, popular cinema, and music not only visualizes complex abstract ideas, it also can trigger a kind of anxious hypnosis that feels like clarity. Errol Morris, one of America’s great documentarians, once tweeted, “I want to be Adam Curtis when I grow up.” But Curtis also has his detractors. His signature style, as well as his methods of argumentation, have been mocked and parodied (most notably in the YouTube video The Loving Trap, and the game “Adam Curtis Bingo“). His broad historical arguments can at times veer towards the conspiratorial, as suggested by the title of last September’s New York Times portrait, “It All Connects: Adam Curtis and the Secret History of Everything.”

The central ideas in HyperNormalization have become all the more relevant in the months since I first saw it last year, with the popular rise of the terms “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and even the “American carnage.” Curtis argues that politicians have not only ceded control to bankers and corporations, they have also given up on changing or even understanding our complex modern world. They’ve replaced that complexity with a unifying simplicity, a fake but simple understanding of the world, that is not only reassuring but also resistant to change from below. On top of that, the political left is now incapable of affecting change due to a general move towards the self, and an accompanying move to self-contained communication bubbles on social media. The rise of those social media bubbles most directly benefits, of course, large corporations.

I can’t help but think about passages in HyperNormalization every time I read today’s headlines or look at my Facebook timeline. The causal chain in Curtis’s narrative is debatable, to say the least. Least convincing, for example, is the alleged move away from political engagement and towards the self among artists in the 1970s, exemplified in the film first by Patty Smith (not persuasive) and Jane Fonda (okay, more persuasive). But Curtis seems to be describing what is going on right now so vividly that certain passages give me chills.

Below is such a passage. It’s hard for me to determine whether Curtis has provided a clear account of a deliberate strategy behind Trump’s tweets and Kelleyanne Conway’s “alternative facts” taken from they playbook of Putin’s advisor, Vladislav Surkov, or whether all of this is just appealing to my own cognitive biases because I find comfort at least in having an explanation of what’s going on. Note that just because A precedes B, doesn’t mean A causes B. But, damn, A and B by themselves are pretty mind bending. It doesn’t even matter if Conway knows Surkov, their tactics seem to parallel each other: defeat the opposition by completely confusing them. (Also note that my point here is distinct from claims about Russian involvement in the elections, which emerged after the film was released.)

Critics of Curtis’s films focus on the interconnectedness of seemingly everything in his broad historical narratives (again, note the New York Times portrait title). Indeed, painting with too broad of a brush can be problematic, and seductive. But one of the many intellectual and aesthetic pleasures associated with Curtis’s films is when he makes some pretty amazing, mind-blowing connections.

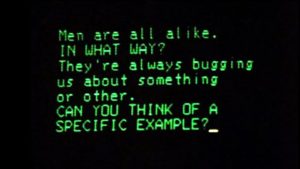

For example, when tracing the history of internet social media bubbles, he discusses the work of Judea Pearl, who worked on Bayesian networks that mimic human behavior. Subsequent work in this field includes Joseph Weizenbaum’s “Eliza” program, which initially was meant to parody attempts to mimic human empathy. Weizenbaum discovered that his colleagues found great comfort in engaging with his program, which was simply designed to reassure them. There are only a few conceptual, historical, and technological steps (via the internet and algorithms) between this and the reassuring comfort of our social network bubbles. But there’s a dark side to that comfort, if your social network has a dark side. Curtis also traces the impact of the internet and computer networks on the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. The mind-blowing connection here is that Judea Pearl’s son was Daniel Pearl, the American journalist whose beheading was videotaped and uploaded on YouTube.

For example, when tracing the history of internet social media bubbles, he discusses the work of Judea Pearl, who worked on Bayesian networks that mimic human behavior. Subsequent work in this field includes Joseph Weizenbaum’s “Eliza” program, which initially was meant to parody attempts to mimic human empathy. Weizenbaum discovered that his colleagues found great comfort in engaging with his program, which was simply designed to reassure them. There are only a few conceptual, historical, and technological steps (via the internet and algorithms) between this and the reassuring comfort of our social network bubbles. But there’s a dark side to that comfort, if your social network has a dark side. Curtis also traces the impact of the internet and computer networks on the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. The mind-blowing connection here is that Judea Pearl’s son was Daniel Pearl, the American journalist whose beheading was videotaped and uploaded on YouTube.

Regardless of whether you find Curtis’s argument persuasive, this is a sublime, transcendent reveal. Maybe not everything is connected, but these two facts are undeniably connected by family ties. It provokes the kind of response that all documentarians aspire to: intellectually enlightening and emotionally provocative. It hearkens back to John Grierson’s definition of documentary: the creative treatment of actuality. Curtis has shaped HyperNormalization for maximum impact, and the results are often breathtaking (for better or worse).

You probably didn’t know the name Judea Pearl, even if you did know the name Daniel Pearl. But Curtis also reminds you about events and details that you did live through and should remember and understand better than you probably do. An extended section of the film traces the rise and fall of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. from irrelevance to bad guy to good guy and back to bad guy. Gaddafi himself never really changed that much, except perhaps in the size of his ego. But Curtis traces these changes and the functions they served in global politics. Again, even taken aside from Curtis’s central argument, these reminders about changes we did live through help us see the past and present more clearly.

Clocking in at 166 minutes, HyperNormalization is intellectually and emotionally exhausting, and probably will be more so if you are already exhausted by news since January 20. Based on the unwavering rhythm and tone, I doubt that Curtis intends anyone to sit through all of it at once. But it is also exciting, often exhilarating filmmaking, even if you reject its central premise.

Check out the other Missed Madison Film Festival reviews for Friday, January 27:

Train to Busan reviewed by Erik Oliver at Madison Film Forum»

The Intervention reviewed by Vincent Mollica (WUD Film Starlight Cinema) at Madison Film Forum»