Review: One Night Only

Review: One Night Only

Belladonna of Sadness | Eiichi Yamamoto | Japan | 1973 | 86 minutes

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Saturday, September 3, 7:00pm»

Mushi Productions’ Belladonna of Sadness pushes to extremes the tension between motion and stillness often found in Japanese animation (“anime”) to great aesthetic effect. James Kreul argues that despite a decidedly 1970s male-fantasy (and a little rapey) take on sex and power, the film delivers a uniquely rich and textured visual experience.

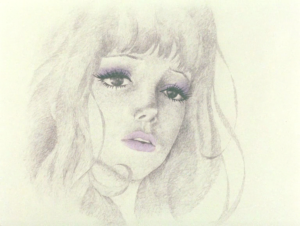

Take a look at the images accompanying this review. They are not from different films. The faces are not different characters. They are all images of Jeanne, the protagonist of the stylistically adventurous Japanese animated feature, Belladonna of Sadness (1973).

Some people dismiss anime because they confuse it aesthetically with the limited animation associated with television production. Belladonna of Sadness is just one example of why this confusion is a profound mistake. The film leads off the strong “Heroines of Anime” series at the UW Cinematheque, which will provide several more examples over the next few weeks.

In the United States, the full animation of the studio production era (Warner Brothers, MGM, etc.) could not be sustained on the meager budgets of television production (Hanna-Barbera, Jay Ward, etc.), thus many regard Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry visually superior to Scooby-Doo and Rocky and Bullwinkle. Chuck Jones dismissed Rocky and Bullwinkle as “illustrated radio.”

In the United States, the full animation of the studio production era (Warner Brothers, MGM, etc.) could not be sustained on the meager budgets of television production (Hanna-Barbera, Jay Ward, etc.), thus many regard Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry visually superior to Scooby-Doo and Rocky and Bullwinkle. Chuck Jones dismissed Rocky and Bullwinkle as “illustrated radio.”

Japanese animation for television faced similar budget constraints, and utilized similar limited animation techniques. But some, like manga-legend-turned-animator Osamu Tezuka, developed at his Mushi Productions a visual aesthetic distinct from American television counterparts. Scholar Marc Steinberg, and others, have argued that proto-anime like Tezuka’s Astro-Boy (1963) utilizes an “economy of motion” that often emphasizes stillness instead of trying to hide the lack of full animation.

Belladonna of Sadness (1973) produced at Mushi Productions shortly after Tezuka’s departure, takes that economy of motion to extremes. At first, it might remind some viewers of an animated variation on the style of Chris Marker’s La Jetée, a film made almost entirely of still images (yes, I know all films are made of still images, but you know what I mean). The dominant stillness throws into relief the motion that we do see, often in just one part of the otherwise still frame. Long sequences of leftward panning over what are essentially static backgrounds are interrupted with sudden bursts of movement and energy.

This isn’t just cutting corners to save money through limited animation. This is a deliberate aesthetic strategy, one which scholar Sheuo Hui Gan has more appropriately labeled “selective animation.” Since many of the individual images do not have to be replicated to produce motion, they have a level of detail and vivid textures not common to traditional cel animation.

The final Mushi Productions features (also A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra) did not completely transform anime, but they have been influential. Around 2006, Toei Animation attempted to jumpstart a genre called “ganime” (“ga” = painting, “nime” = anime). The best known example of ganime might be Fantascope Tylostoma (2006), which you can watch in an unsubtitled version on YouTube and easily notice the influence. Because Belladonna of Sadness represents a path generally not taken, however, watching it in 2016 remains a refreshingly eye-opening experience.

The final Mushi Productions features (also A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra) did not completely transform anime, but they have been influential. Around 2006, Toei Animation attempted to jumpstart a genre called “ganime” (“ga” = painting, “nime” = anime). The best known example of ganime might be Fantascope Tylostoma (2006), which you can watch in an unsubtitled version on YouTube and easily notice the influence. Because Belladonna of Sadness represents a path generally not taken, however, watching it in 2016 remains a refreshingly eye-opening experience.

The plot of Belladonna is a psychosexual fairytale. Jean and Jeanne, a young couple sometime, someplace in the European middle ages*, are about to consummate their love shortly after their marriage. But first they follow tradition and make an offering to their local baron as a token of their gratitude. The greedy baron, however, demands much more than Jean can offer. When Jean cannot pay, the baron and members of his court proceed to gang rape Jeanne.

As Jeanne attempts to recover, she encounters a small demon who gradually gives Jeanne more and more power. Before Jeanne can fully stand up to the power of the baron, she must give herself willingly to the demon, which she eventually does. In a cave outside of the village, she establishes a haven for hedonism, and appeals to the villagers by solving many of their problems with the power of a magical Belladonna flower. Most of the last half of the film is a battle for power and influence between the corrupt baron and the polymorphously perverse Jeanne.

As you can probably sense, some of this is more than a little rapey. It’s never as graphic as tentacle hentai, but the film shares some of the same attitudes about the delicacies of violating a woman’s body. Interestingly, the image accompanying the film’s synopsis on the Cinematheque website illustrates this: Jeanne’s body is ecstatically ripped apart during the opening rape. The aesthetic abstraction is almost more disturbing than an literal representation. While the overall concept of the “Heroines of Anime” series is admirable (as discussed at LakeFrontRow), one should keep in mind that the representation of women in some of these films, even when they are protagonists, are full of ideological tensions and contradictions that are occasionally problematic.

As you can probably sense, some of this is more than a little rapey. It’s never as graphic as tentacle hentai, but the film shares some of the same attitudes about the delicacies of violating a woman’s body. Interestingly, the image accompanying the film’s synopsis on the Cinematheque website illustrates this: Jeanne’s body is ecstatically ripped apart during the opening rape. The aesthetic abstraction is almost more disturbing than an literal representation. While the overall concept of the “Heroines of Anime” series is admirable (as discussed at LakeFrontRow), one should keep in mind that the representation of women in some of these films, even when they are protagonists, are full of ideological tensions and contradictions that are occasionally problematic.

I do not mention this as a “trigger warning” (a practice that I generally oppose). In fact, isolating the rape issue runs the risk of oversimplifying the very complex representation of sexuality in Belladonna of Sadness. That complexity, even when it occasionally offends, is worth watching, contemplating, and discussing.

While I would argue that Belladonna is male fantasy (and sometimes a juvenile one), the seemingly unbounded hedonism occasionally breaks down sexual binaries. One particularly memorable sequence features not only a daisy chain of sexual partners and positions, but also quick pencil sketches of physical transformations where genitalia morph into non-human forms. While the nod to feminism in the film’s coda is almost laughably forced, the film does convey an understanding of the power dynamics of sexuality and politics.

Another memorable montage follows Jeanne’s physical submission, body and soul, to the demon. Her pleasure is suggested in a mind-blowing montage that explodes out of 1970s pop culture rather than the diegesis of the European middle ages. The imagery really comes out of nowhere, but the kinetic energy is irresistible. It’s the most obviously dated sequence, suggesting connections to Peter Max, René Laloux, Ralph Bakshi, and Yellow Submarine. It’s also the sequence most in sync stylistically with the film’s ongoing heavy-base score (by avant-garde jazz composer Masahiko Satoh).

Another memorable montage follows Jeanne’s physical submission, body and soul, to the demon. Her pleasure is suggested in a mind-blowing montage that explodes out of 1970s pop culture rather than the diegesis of the European middle ages. The imagery really comes out of nowhere, but the kinetic energy is irresistible. It’s the most obviously dated sequence, suggesting connections to Peter Max, René Laloux, Ralph Bakshi, and Yellow Submarine. It’s also the sequence most in sync stylistically with the film’s ongoing heavy-base score (by avant-garde jazz composer Masahiko Satoh).

Belladonna of Sadness was never officially released theatrically in the United States, so this 4K restoration playing at the Cinematheque represents the first opportunity for many Americans to see the film on the big screen. (Distributor Cinelicious Pics has been touring the film since this past May.) It’s a no-brainer as the pick of the weekend, not only for the spectacle on screen, but also for the potential responses of the easily offended.

* Probably France, based on Jean’s name and the very odd coda to the film.