Review: One Screening Only

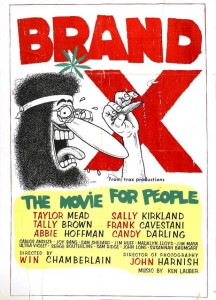

Brand X | Wynn Chamberlain | USA | 1969 | 87 min

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Saturday, March 21, 4:00pm»

Wynn Chamberlain’s Brand X is an valuable reminder of many forgotten aspects of the 1960s counterculture, including its influence on current mainstream humor.

The New York Times obituary for artist, author, and filmmaker Wynn Chamberlain last December describes his long lost film, Brand X, as a “cheerily vulgar parody of television programming and advertising.” The juxtaposition of “cheerily” and “vulgar” might seem like an odd choice, but it captures the playful and sexually explicit qualities of this countercultural comic revue. Shot in 1969 and screened only a few times in 1970 before “disappearing,” Brand X stands somewhere on the continuum from the underground films of Andy Warhol and Robert Downey, Jr, through the early features of John Waters on the Midnight Movie college circuit, to the first season of the Not Ready for Prime Time Players on Saturday Night LIve.

We can now discuss where Brand X might be on that continuum because it has been restored by the Cineteca di Bologna, and a DCP of the film will be screened on Saturday afternoon as part of the UW Cinematheque’s program from the Il Cinema Ritrovato (“Rediscovered cinema”) festival. And while discussing its place in film history is important, what’s more important is that we can watch Brand X once again, because it is pretty damn funny.

The key figure here is Taylor Mead, who was the clown prince of the underground film. Chamberlain and Mead were part of the Warhol entourage that drove to the west coast in 1963, which resulted in Tarzan and Jane Regained, Sort of, a travelogue that wast the closest Warhol came to making a lyrical beat film. When a critic of that film wrote that he didn’t want to see “two hours of Taylor Mead’s ass,” Warhol responded with the film Taylor Mead’s Ass (1964). But even before his collaborations with Warhol, Mead was well recognized in underground films starting with Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief (1960). Mead’s unique comic abilities were utilized by filmmakers ranging from Adolphas Mekas (Hallelujah the Hills, 1963) to Robert Downey, Sr. (Babo 73, 1964), and he appears briefly in Midnight Cowboy (1969) to give the party scene some underground legitimacy.

What’s so special about Mead? All you have to do is point the camera at him and he’s captivating and entertaining. His long face suggests a sad clown without makeup, and his warbly voice often trails off into non sequiturs. An early scene is Brand X casts him as a television fitness show host, and all he needs as a prop is a chair to make the scene funnier than it should be for longer than it should be. While Chamberlain gives himself a writing credit, he makes sure to point out that Mead’s improvisations are his own.

Brand X features Mead and a collection of performers and actors—including several Warhol superstars and Sally Kirkland, who years later would be nominated for an Academy Award for Anna (1987)—appearing in a series of spoofs on television and popular culture. In terms of production values and style, it recalls the later Warhol exploitation films with poorly recorded sound. But here we occasionally have post-production audio tracks (including music that sometimes drowning out the original audio), optical titles, and even excessive cross cutting (which would have been shocking in a Warhol film). The post-production techniques could be done by anyone with a laptop now, but at the time they would have required at least some professional resources.

Brand X features Mead and a collection of performers and actors—including several Warhol superstars and Sally Kirkland, who years later would be nominated for an Academy Award for Anna (1987)—appearing in a series of spoofs on television and popular culture. In terms of production values and style, it recalls the later Warhol exploitation films with poorly recorded sound. But here we occasionally have post-production audio tracks (including music that sometimes drowning out the original audio), optical titles, and even excessive cross cutting (which would have been shocking in a Warhol film). The post-production techniques could be done by anyone with a laptop now, but at the time they would have required at least some professional resources.

Content wise the clear precedent is Robert Downey, Sr.’s parody of the advertising industry, Putney Swope (1969), in this case jettisoning the narrative and focusing on skits and fake ads. The film has the feel of a low-budget version of Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), but I was also struck by how similar it is to Saturday Night Live, which debuted in 1975. Many SNL tropes are here: fake talk show, fake game show, and of course fake ads. Since it was rarely screened, Brand X clearly wasn’t a direct influence on SNL, but just as clearly Brand X, Kentucky Fried Theater and SNL emerged from the same strands of the 1960s counterculture. (I’m confident this idea will be explored in the Wisconsin Film Festival presentation of Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Story of the National Lampoon). In Brand X, instead of the Bass-o-matic, we have ads for dirt (“Is your house too clean? Use dirt.”), food (“Eat more. Think less.”), vibrators (“Don’t let people rub you the wrong way, do it yourself”), and of course, balling.

Yep, there’s plenty of good old fashioned, back-to-nature hairy-assed hippie balling on display in Brand X (you can get a sense of that from the not-safe-for-work trailer below). Well, the ad for balling actually takes place on the trunk of a moving car, but the car is driving out in nature. While the attitudes about sexuality, drugs, and race are certainly dated, they also make Brand X all the more interesting and valuable as a document of the times. There’s some stuff here that many of us don’t remember, and younger people probably never knew about, like EST-style screaming. While the explicit sexual content is hetero, there are plenty of direct and indirect references to gay subculture. The more explicit material suggests another comic lineage that leads to the Midnight Movie circuit and John Waters.

As interesting as Brand X is historically, the main reason to go see it on Saturday afternoon is that it is very funny. Even when it is not laugh-out-loud funny or awkwardly dated, it is always effortlessly charming and good natured. The film’s tagline is “The movie for people,” which then as now is very different than a movie for the masses. Brand X still feels like an invitation to be a part of something.