Camille Claudel 1915 (Bruno Dumont, France, 2013, 95 min)

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Fri Jan 24 @ 7pm»

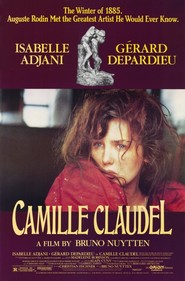

Bruno Dumont’s Camille Claudel 1915 begins with a series of title cards that very quickly explain Claudel’s background as an artist, her romantic relationship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin, and her relationship with her younger brother, the writer Paul Claudel. We also learn that after she lived reclusively for 10 years, her family sent her to a series of asylums. That’s a lot to summarize in a life as interesting as Claudel’s, and it might seem odd to begin a film about her at “the end,” after her artistic achievements and dramatic relationships. (For a more conventional biopic approach, check out the link below for Bruno Nuytten’s 1988 film, Camille Claudel). But Dumont and Binoche seem to be after something different than a conventional biopic here. Together they explore the life of an artist isolated from her art, which does not make her less of an artist.

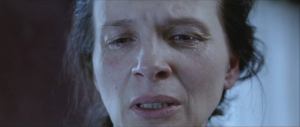

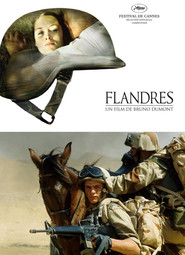

My experience with Dumont’s films is limited to his war and romance film Flanders (2006), and his religion-mixed-with-politics drama Hadewijch (2009), both of which feature a relatively bleak world view. In fact, the outright brutality in Flanders led me to expect a loud and oppressive ordeal in Claudel’s asylum. I was pleasantly surprised that the strongest sequences of Camille Claudel 1915 are actually very quiet and subtle. In many ways the film is about Claudel’s eyes, and by extension it is structured around Juliette Binoche’s performance. Almost everything about her performance reminds us what Claudel is not doing: she is not creating, and it is slowly killing her.

A few sequences in particular highlight this theme and showcase Binoche’s peak skills. In the opening sequence Claudel receives a bath and the attendant comments on how dirty her hands are. The subtle shift on Binoche’s face at this moment crystalizes the entire film: Claudel wants her hands to be even dirtier, in the act of creating art. This resonates later when we discover why her hands are often dirty. On the asylum grounds she comes across a clump of mud that in her hands quickly transforms into artist’s clay. Every squeeze of the clay has the energy of the spark of creation, but she has to abandon it in the field, and keep her hands clean.

Another impressive quiet sequence begins with Claudel sitting in a chair facing a window with sunlight streaming in. One could imagine a cliched reading of the shot that would interpret the shadows of the window acting like bars of a prison. Instead of the shadows, however, Claudel’s eyes help guide us to the sunlight, and it is her observation of the light that structures the sequence. In a series of shot/reverse shots, we watch her examine the room with an artist’s eyes, observing the textures created as the light hits different surfaces. Eventually her eyes fall upon two fellow patients at the asylum, and we see them as an artist would see the subjects of a portrait. Claudel’s living conditions were oppressive, particularly for an artist, but the film shows how she tried to cope by using the artist’s tools that they could not take away from her: her eyes and her powers of observation.

Another impressive quiet sequence begins with Claudel sitting in a chair facing a window with sunlight streaming in. One could imagine a cliched reading of the shot that would interpret the shadows of the window acting like bars of a prison. Instead of the shadows, however, Claudel’s eyes help guide us to the sunlight, and it is her observation of the light that structures the sequence. In a series of shot/reverse shots, we watch her examine the room with an artist’s eyes, observing the textures created as the light hits different surfaces. Eventually her eyes fall upon two fellow patients at the asylum, and we see them as an artist would see the subjects of a portrait. Claudel’s living conditions were oppressive, particularly for an artist, but the film shows how she tried to cope by using the artist’s tools that they could not take away from her: her eyes and her powers of observation.

At times Dumont seems a bit too fond of dwelling on the spectacle of mental illness, often drawing a sharp contrast between Claudel and the more obvious physical symptoms of her fellow patients. The presentation of the mentally ill is not much more sophisticated than Claudel’s own when she calls her fellow patients “creatures.” And as the film goes on, one could almost make the similar argument about the contrasts between Claudel and those taking care of her; they are never developed significantly beyond the gentle caretakers and the perhaps aloof academic physicians. In one reaction shot of her doctor, his gaping mouth stays open for so long without any other movement that one starts to think that the shot is an intentional joke that goes flat.

At times Dumont seems a bit too fond of dwelling on the spectacle of mental illness, often drawing a sharp contrast between Claudel and the more obvious physical symptoms of her fellow patients. The presentation of the mentally ill is not much more sophisticated than Claudel’s own when she calls her fellow patients “creatures.” And as the film goes on, one could almost make the similar argument about the contrasts between Claudel and those taking care of her; they are never developed significantly beyond the gentle caretakers and the perhaps aloof academic physicians. In one reaction shot of her doctor, his gaping mouth stays open for so long without any other movement that one starts to think that the shot is an intentional joke that goes flat.

The film works best in its quiet observational moments, but the plot concerns the impending visit from Camille’s brother, Paul. The film presents him being as verbose as his sister is observant, and most of what he says is philosophical or theological in nature. His introduction breaks the interesting visual rhythm that the film had established, and the last third of the film suffers from his presence rather than providing a strong dramatic conflict with Camille. When they finally meet, he cannot seem to communicate with her without obtuse literary language, which removes much of the energy of the scene.

In terms of staging, it is interesting that Camille’s (and Binoche’s) strongest moment in the scene is when she has her back turned to Paul. Her eyes and face have structured most of the film, but now Dumont and Binoche really pull out the stops with the tightest close up of the entire film. It is almost jarring when we cut back to Paul, because this is her moment and he seems almost superfluous. The emotional payoff to the scene again comes from simply watching Binoche, rather than listening to what either Claudel has to say.

Despite those reservations it is certainly worth catching the film on the big screen as part of the Cinematheque’s Premiere Showcase. For more perspectives on the film, my colleague Jake Smith has posted some additional reviews (including negative ones) on our Flipboard magazine. And for those interested in streaming follow-up films, below I have posted links to Dumont’s Flanders on Netflix View Instantly and Camille Claudel on Amazon Instant Video. If you miss the screening, you can queue Camille Claudel 1915 at GoWatchIt to receive updates when it is available on home video or streaming outlets.

Synopses and Posters from The Movie Database

Flanders (Bruno Dumont, France, 2006, 91 min)»

Flanders (Bruno Dumont, France, 2006, 91 min)»

André Demester secretly and painfully loves Barbe, his childhood friend, accepting from her the little that she gives him. He leaves home to be a soldier in a war in a far off land. Barbarity, camaraderie and fear turn him into a warrior. As the seasons go by, Barbe, alone and wasting away, waits for the soldiers to return. Will Demester’s boundless love for Barbe save him?

Camille Claudel (Bruno Nuytten, France, 1988, 175 min)»

Camille Claudel (Bruno Nuytten, France, 1988, 175 min)»

The life of Camille Claudel, a french scupltor who becomes the apprentice of Auguste Rodin and later his lover. Her passion for her art and Rodin drive her further away from reason and rationality.