Croupier (Mike Hodges, UK, 1998, 94 min.)

Croupier (Mike Hodges, UK, 1998, 94 min.)

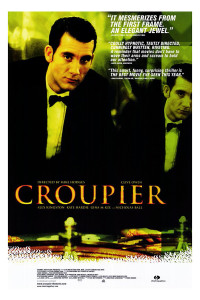

![]() “The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling—a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension—becomes unbearable and the senses awake and revolt from it.” —Ian Fleming, Casino Royale, Chapter 1 Amongst the many hallmarks of the James Bond films, one that I believe is seldom talked about is what I call “the casino walk”—a scene that each of the Bond actors has in at least one of his films, in which he ambles across a casino floor. At the level of performance, these scenes are emblematic of the particular actors’ take on the character in many cases, from Connery’s suave, relaxed stride to Craig’s arrogantly menacing approach. And yet, to this day, I can’t shake the notion that of all people, the one to get it 100% right never played James Bond at all.

“The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling—a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension—becomes unbearable and the senses awake and revolt from it.” —Ian Fleming, Casino Royale, Chapter 1 Amongst the many hallmarks of the James Bond films, one that I believe is seldom talked about is what I call “the casino walk”—a scene that each of the Bond actors has in at least one of his films, in which he ambles across a casino floor. At the level of performance, these scenes are emblematic of the particular actors’ take on the character in many cases, from Connery’s suave, relaxed stride to Craig’s arrogantly menacing approach. And yet, to this day, I can’t shake the notion that of all people, the one to get it 100% right never played James Bond at all.  The actor is Clive Owen. The film is Croupier, which introduced many of us to this British actor, who presently stars in Steven Soderbergh’s new television series, The Knick. As the years have passed, I have always been interested in Mr. Owen’s choices as an actor, from the airy Greenfingers, to the sublime Children of Men, to the indefensible Shoot ‘em Up. There remains something very special about Croupier, though, both in terms of Owen’s performance and the film itself.

The actor is Clive Owen. The film is Croupier, which introduced many of us to this British actor, who presently stars in Steven Soderbergh’s new television series, The Knick. As the years have passed, I have always been interested in Mr. Owen’s choices as an actor, from the airy Greenfingers, to the sublime Children of Men, to the indefensible Shoot ‘em Up. There remains something very special about Croupier, though, both in terms of Owen’s performance and the film itself.  Croupier begins with Jack Manfred (Owen) in search of a job and a publisher for his novel. Jack’s father urges him to seek employment as a croupier/dealer in a local casino, a world with which Jack is all too familiar and has done his utmost to avoid. But like any hapless gambler, even a former croupier can be drawn back into the “house of addiction.” While his girlfriend (Gina McKee) tries her best to hold on to him, Jack slips further and further into the grip of the casino and its parade of shady characters, including a damsel-in-distress (brilliantly played by Alex Kingston of Doctor Who fame) who is, naturally, far more than she seems. As a writer, Jack observes everything around him, trying to remain a “detached voyeur,” but he soon realizes that he is becoming Jake, the thinly-veiled fictional alter-ego he is creating for his new novel.

Croupier begins with Jack Manfred (Owen) in search of a job and a publisher for his novel. Jack’s father urges him to seek employment as a croupier/dealer in a local casino, a world with which Jack is all too familiar and has done his utmost to avoid. But like any hapless gambler, even a former croupier can be drawn back into the “house of addiction.” While his girlfriend (Gina McKee) tries her best to hold on to him, Jack slips further and further into the grip of the casino and its parade of shady characters, including a damsel-in-distress (brilliantly played by Alex Kingston of Doctor Who fame) who is, naturally, far more than she seems. As a writer, Jack observes everything around him, trying to remain a “detached voyeur,” but he soon realizes that he is becoming Jake, the thinly-veiled fictional alter-ego he is creating for his new novel.  All of the supporting players are well cast and well utilized, but Owen owns the screen whenever he’s on it, which is to say virtually the whole film. His mix of cool indifference and sharp wit, and the way he effortlessly shifts between the two were utterly beguiling at the time, and happily remain so after multiple viewings. The film’s voiceover—Jack talking to the audience in the third person, writing his own story for us as he goes—is especially enjoyable not only because it is a smart variation on a typical film noir device, but also because of the hypnotic tone of Clive Owen’s voice (a quality other directors would leverage with voiceover in their movies, Sin City being a prime example). And that walk through the casino? With it, he turns the den of iniquity into his kingdom, and makes the “punters” even more his subjects. Croupier is directed by Mike Hodges, who has quite a distinctive career himself. If one looks at

All of the supporting players are well cast and well utilized, but Owen owns the screen whenever he’s on it, which is to say virtually the whole film. His mix of cool indifference and sharp wit, and the way he effortlessly shifts between the two were utterly beguiling at the time, and happily remain so after multiple viewings. The film’s voiceover—Jack talking to the audience in the third person, writing his own story for us as he goes—is especially enjoyable not only because it is a smart variation on a typical film noir device, but also because of the hypnotic tone of Clive Owen’s voice (a quality other directors would leverage with voiceover in their movies, Sin City being a prime example). And that walk through the casino? With it, he turns the den of iniquity into his kingdom, and makes the “punters” even more his subjects. Croupier is directed by Mike Hodges, who has quite a distinctive career himself. If one looks at this film as being from the same man who directed Get Carter, then Croupier comes not quite so out of nowhere. (If one looks at it as being from the same man who directed Flash Gordon, on the other hand…) Unlike Scorsese’s Casino, Hodges opts for a less flashy and more restrained style. His staging is precise if not terribly elaborate, and his camera movement full of careful zooms and impressively gentle pans. Admittedly, some of the production design is a little dated, but A) show me a 1990s film where that isn’t the case, and B) it plays to one of the film’s central strengths, referring back to the Fleming quote at the beginning of this post. Hodges has imbued his film with a visual style that complements the script, pulling no punches in its rendering of casinos as places where the fleeting allure of polished chintz gives way to slow, vile, and irrevocable self-destruction. Speaking of the script, I remain struck by the pre-title director credit. It doesn’t read, “A Mike Hodges Film.” Instead, it reads, “A Mike Hodges and Paul Mayersberg Film,” quite aptly giving due credit to Mayersberg’s impeccably constructed script. In the published script, Mayersberg (who also scripted The Man Who Fell to Earth and Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) cites myriad influences, from Jean-Pierre Melville and Bresson’s Pickpocket to Mickey Spillane and Vladimir Nabokov. However, even with these acknowledged influences and more, the script thankfully comes off not as a catalog of references but as unmistakably fresh. Knowing just where to tighten the plot, and where to loosen it with ambiguity, Mayersberg’s script plays like a great poker game: well calculated, but allowing for the occasional lucky (or unlucky) deal that can make one player and break another. He allows his characters to use jargon naturally, and he trusts you enough that you’ll make your way through the world he presents without his characters having to explain in condescendingly awkward detail what each term means. Would that more screenwriters (and filmmakers in general) trusted their audiences as much. As far as I know, since there is no Blu-Ray of this film, and the quality of the DVD is unforgivable (i.e. non-anamorphic), streaming the film in HD through Netflix really is the best way to see it at home. While we here at the Madison Film Forum love bringing you reviews of and reflections on films playing in theaters in the area, we’d be remiss if we didn’t highlight some of the films that are the mere push of a button away, especially ones that may have slipped under your radar. For my part, especially if you like your movies intelligent and hard-boiled, Croupier is one of the surest bets there is.

this film as being from the same man who directed Get Carter, then Croupier comes not quite so out of nowhere. (If one looks at it as being from the same man who directed Flash Gordon, on the other hand…) Unlike Scorsese’s Casino, Hodges opts for a less flashy and more restrained style. His staging is precise if not terribly elaborate, and his camera movement full of careful zooms and impressively gentle pans. Admittedly, some of the production design is a little dated, but A) show me a 1990s film where that isn’t the case, and B) it plays to one of the film’s central strengths, referring back to the Fleming quote at the beginning of this post. Hodges has imbued his film with a visual style that complements the script, pulling no punches in its rendering of casinos as places where the fleeting allure of polished chintz gives way to slow, vile, and irrevocable self-destruction. Speaking of the script, I remain struck by the pre-title director credit. It doesn’t read, “A Mike Hodges Film.” Instead, it reads, “A Mike Hodges and Paul Mayersberg Film,” quite aptly giving due credit to Mayersberg’s impeccably constructed script. In the published script, Mayersberg (who also scripted The Man Who Fell to Earth and Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) cites myriad influences, from Jean-Pierre Melville and Bresson’s Pickpocket to Mickey Spillane and Vladimir Nabokov. However, even with these acknowledged influences and more, the script thankfully comes off not as a catalog of references but as unmistakably fresh. Knowing just where to tighten the plot, and where to loosen it with ambiguity, Mayersberg’s script plays like a great poker game: well calculated, but allowing for the occasional lucky (or unlucky) deal that can make one player and break another. He allows his characters to use jargon naturally, and he trusts you enough that you’ll make your way through the world he presents without his characters having to explain in condescendingly awkward detail what each term means. Would that more screenwriters (and filmmakers in general) trusted their audiences as much. As far as I know, since there is no Blu-Ray of this film, and the quality of the DVD is unforgivable (i.e. non-anamorphic), streaming the film in HD through Netflix really is the best way to see it at home. While we here at the Madison Film Forum love bringing you reviews of and reflections on films playing in theaters in the area, we’d be remiss if we didn’t highlight some of the films that are the mere push of a button away, especially ones that may have slipped under your radar. For my part, especially if you like your movies intelligent and hard-boiled, Croupier is one of the surest bets there is.