Domestic (Adrian Sitaru, Romania, 2013, 85 min)

Domestic (Adrian Sitaru, Romania, 2013, 85 min)

Wisconsin Film Festival, Friday, April 4, 4:30pm & Saturday, April 5, 4:30pm»

Since 2000, it usually takes the Wisconsin Film Festival or campus screenings for recent Romanian cinema to come through town. But those paying attention have probably noticed a trend towards slow-paced long takes and gritty realism from Romanian directors including Cristi Puiu (The Death of Mr. Lazarescu; Aurora) and Corneliu Porumboiu (12:08 East of Bucharest; Police, Adjective) Cristian Mungiu (4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days; Beyond the Hills). Adrian Sitaru has certainly learned lessons from his colleagues, but with his film Domestic he uses the long take as a building block in a genuinely engaging—and surprisingly colorful and bright—cinematic puzzle. But what makes Domestic more emotionally satisfying than a mere formal exercise is that as you complete the puzzle, you realize that this seemingly quirky comic mix of eccentric neighbors and their animals (pets and food) is actually a meditation on death, loss, grief, and regret.

Broadly speaking, the plot of Domestic concerns the interrelated stories of residents in an apartment complex, led by Mr. Lazar, who is the neighborhood administrator. But Domestic features three narrative techniques that make a straight forward plot synopsis problematic. First, we see some things that we don’t understand until they are explained much later, like the opening shot of a funeral. This funeral is seen in a point-of-view shot, but we don’t know whose point-of-view, or what is actually going on, until it is explained to us much later. When it is explained, the funeral is something very different than what we initially inferred.

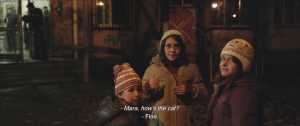

Second, we see some details and events that we don’t realize are significant until much later. In the film’s second shot, also in point-of-view, three girls say “Hello” to Toni. We might now infer that the first funeral shot is also Toni’s point of view, but we have not seen his face, so we don’t know who he is. Toni asks Mara, “How’s the cat?” and she replies, “Fine.” This seems to be a throw away detail, because the rest of the shot concerns a discussion with Mr. Lazar and other residents about what do do with the Barbu family’s dog, who is causing problems in the apartment complex. But we will discover later that the crucial piece of information is that Mara has a cat, and we need to remember that information despite relatively little redundancy from the film.

Finally, there are crucial story events that we do not see on screen, and we must very quickly make inferences and connections between what we know from previous scenes and what we subsequently see and hear to understand what we’ve missed. So despite the fact that we do see a lot of things happen in the long takes, the long takes don’t show us everything we need to know to piece together the story.

You might assume, incorrectly in this case, that a long take film would present all the information you need in visual terms. But these three techniques also surprise you because the long takes themselves have a quirky, manic energy that make them hard to keep up with. This is best illustrated with a tour-de-force of long take staging early in the film, in a scene in Mr. Lazar’s apartment with his family. The shot is 10 minutes and 50 seconds long (!), and the camera remains in one spot in the kitchen with only reframing tilt and pan movements.

The basic action in the scene centers around Mrs. Lazar bringing home a live chicken, and a debate about how it should be killed and by whom. Once Mrs. Lazar puts the chicken in the bathroom, there is great interplay between the foreground (Mara at the kitchen table), middle ground (the apartment door) and background (the bathroom). The comic-drama in the scene quickly becomes whether or not Mara will kill the chicken. She walks back and forth between her table and the bathroom, occasionally with a knife, but like a tableau in a classic stage melodrama, the suspense over whether she will actually kill the chicken is drawn out to nearly absurd lengths. Of course, when the killing finally takes place, it is in the extreme background, so as Mara washes her knife the only hint of the violence that we can actually see is the blood stains on the far bathroom wall. The inversion of traditional staging (usually you want the action to be in the foreground) parallels the way that the narration also makes you work a bit harder to understand the important details of the story.

Eventually the Lazars are visited by Toni and another neighbor, Mr. Mihaes, who reveal a plot to take care of Mr. Barbu’s dog by simply dog-napping him and taking him to a shelter. Again we have great interplay between the planes of action, now centering on the middle ground (the Lazars make sure that they close the bathroom door before letting the visitors in). With Toni’s presence in the middle ground, we are finally able to confirm his identity. We had seen his face in a previous shot, but with no way of confirming his identity. Now, finally, we can confirm his identity because he is addressed as Toni, and because he discusses Mara’s cat with Mr. Lazar. Buried in the middle of this long take that focuses on the killing of the chicken and the plot for Mr. Barbu’s dog is an essential piece of information: Toni gave Mara a cat, and offers to take it back, but Mr. Lazar decides to keep it because Mara is already attached to it. This doesn’t seem particularly important at the time, but as the film goes on you will need to remember this and connect it to new details as they are revealed. The extra work you have to do to make these connections is part of the pleasure of watching the film. I was reluctant at first to give you a little bit of a hint about the cat—some might consider this a borderline spoiler. But this isn’t the only example of the attention you need to pay to the details, so there is plenty of fun to be had now that you know what the game will be.

After this epic long take in Mr. Lazar’s kitchen, Domestic continues to surprise you with variations in style. In one direction, some shots are even more minimal in movement and staging. A great dinner scene in Mr. Mihaes’s apartment lines up all of the heads across the wide cinemascope screen; from the still image (above) you would think that this staging would seem too awkward or forced, but it has its own kind of flow and manic energy. In the other direction—again, I’m almost reluctant to reveal this because of the impact that it has when you first see it—you also have some elaborately staged and choreographed camera movements, which in their context punctuate emotionally important moments. One sometimes forgets how much impact a relatively simple camera movement can have until such movements are only used sparingly and with great purpose. The impact of these camera movements in Domestic is in part due to the minimalist style through most of the film.

After this epic long take in Mr. Lazar’s kitchen, Domestic continues to surprise you with variations in style. In one direction, some shots are even more minimal in movement and staging. A great dinner scene in Mr. Mihaes’s apartment lines up all of the heads across the wide cinemascope screen; from the still image (above) you would think that this staging would seem too awkward or forced, but it has its own kind of flow and manic energy. In the other direction—again, I’m almost reluctant to reveal this because of the impact that it has when you first see it—you also have some elaborately staged and choreographed camera movements, which in their context punctuate emotionally important moments. One sometimes forgets how much impact a relatively simple camera movement can have until such movements are only used sparingly and with great purpose. The impact of these camera movements in Domestic is in part due to the minimalist style through most of the film.

Nearly every shot has an animal of some kind in it, and another game becomes whether you can guess what animal will be relevant for a new scene, and how they will enter the shot. But perhaps the more important game to play is to quickly infer what you have missed between shots, in terms of narrative events and changes in relationships. Again, Mara’s cat becomes an important tool to piece together some very significant events and changes in the Lazar household.

I’ll end where the film begins and ends: the funeral scene. One last technique worth mentioning is repetition: once we learn from Toni what the funeral scene is, we actually hear his explanation repeated several times as he describes the funeral to several characters. By the time we see the entire funeral scene at the very end of the film, we have memorized what happens, and we anticipate each bit of action in the scene as it plays out for the viewer. However, we also discover a new piece of information that Toni has left out of each of his descriptions. This last detail, and this last image of the film, is very moving because of what we have pieced together from what Toni has said and more importantly has not said about the funeral. This very simple last image, punctuated with a gently floating camera movement, is one of the great final shots in recent memory, and certainly the best last shot of the films I’ve previewed for the 2014 Wisconsin Film Festival.