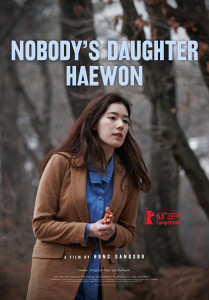

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon (Hong Sang-soo, South Korea, 2013, 90 min)

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon (Hong Sang-soo, South Korea, 2013, 90 min)

Wisconsin Film Festival, Saturday April 5, 9:15pm & Tuesday April 8, 3:00pm»

As I mentioned in my post covering some of this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival’s “Big Auteurs,” Hong Sang-soo was previously a blind spot in my movie watching history. I was intrigued by descriptions of his style—long takes, playful structures, and heavy on conversation. After viewing his some of his more recent works like In Another Country, Hahaha, and Oki’s Movie, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that a little can go a long way (put it this way, I wouldn’t recommend binge-watching these). That said, Hong’s latest work, Nobody’s Daughter Haewon, is a satisfying experience overall.

On the surface, the movie concerns itself with the emotional turmoil of its titular character Haewon, played with heartbreaking strength and delicacy by Jung Eun-chae. Depressed by the departure of her mother, who is moving to Canada, Haewon reestablishes her previous relationship with a married professor (Lee Sun-kyun). In so doing, instead of overcoming her sadness at her mother’s departure, she sinks even further into that sadness. Haewon narrates the story for the audience via voiceover in conjunction with shots of her writing in her journal, and here is one of the major aspects that differentiate the film from the run-of-the-mill lovelorn tale. The movie begins with a dream (Haewon’s chance meeting with actress Jane Birkin, who plays herself), and shifts from memory to dream to back to memory. Hong deftly plays with the audience’s perceptions of what is imagined, what is remembered, and what is present, giving viewers a structure that becomes as reflexive as the story is reflective.

On the surface, the movie concerns itself with the emotional turmoil of its titular character Haewon, played with heartbreaking strength and delicacy by Jung Eun-chae. Depressed by the departure of her mother, who is moving to Canada, Haewon reestablishes her previous relationship with a married professor (Lee Sun-kyun). In so doing, instead of overcoming her sadness at her mother’s departure, she sinks even further into that sadness. Haewon narrates the story for the audience via voiceover in conjunction with shots of her writing in her journal, and here is one of the major aspects that differentiate the film from the run-of-the-mill lovelorn tale. The movie begins with a dream (Haewon’s chance meeting with actress Jane Birkin, who plays herself), and shifts from memory to dream to back to memory. Hong deftly plays with the audience’s perceptions of what is imagined, what is remembered, and what is present, giving viewers a structure that becomes as reflexive as the story is reflective.

This film shares many commonalities with Hong’s other recent pictures: a professor and/or filmmaker who is romantically involved with a student, beautiful and austere long-take cinematography punctuated by reframing through zooms, complex narrative structure, scenes of people drinking (often soju, and often to drunkenness) or taking wandering walks (often through parks), and a tonal mix of the comedic and the melancholic. The story, while well acted and ultimately well told, can occasionally feel more dreary than methodical in pace. The film’s style and structure do mitigate that dreariness, though (a dreariness that I admit may also have arisen from watching several of Hong’s films in a short space of time).

This film shares many commonalities with Hong’s other recent pictures: a professor and/or filmmaker who is romantically involved with a student, beautiful and austere long-take cinematography punctuated by reframing through zooms, complex narrative structure, scenes of people drinking (often soju, and often to drunkenness) or taking wandering walks (often through parks), and a tonal mix of the comedic and the melancholic. The story, while well acted and ultimately well told, can occasionally feel more dreary than methodical in pace. The film’s style and structure do mitigate that dreariness, though (a dreariness that I admit may also have arisen from watching several of Hong’s films in a short space of time).

Hong’s investment in life’s little moments and how he situates them within the film’s structure are compelling not only in this film but his work as a whole. For example, in one scene, a character tosses a cigarette down on the pavement—a wholly mundane gesture. We then enjoy a scene where Haewon and her mother have an amusing exchange with a man outside a shop. Fast forward 40 or 50 minutes, where we see Haewon walk back to that same shop and step on a burning cigarette that graphically matches the one we saw earlier. Only this time, it belongs to a completely different person. In that moment, because Hong has already seamlessly woven dream and reality together, we ask ourselves whether we have moved back into a dream, or if this is merely the image of a dream become reality. It is reminiscent of In Another Country, wherein Hong leaves seemingly throwaway moments that reappear and establish a sort of continuity between three completely separate stories.

Hong’s investment in life’s little moments and how he situates them within the film’s structure are compelling not only in this film but his work as a whole. For example, in one scene, a character tosses a cigarette down on the pavement—a wholly mundane gesture. We then enjoy a scene where Haewon and her mother have an amusing exchange with a man outside a shop. Fast forward 40 or 50 minutes, where we see Haewon walk back to that same shop and step on a burning cigarette that graphically matches the one we saw earlier. Only this time, it belongs to a completely different person. In that moment, because Hong has already seamlessly woven dream and reality together, we ask ourselves whether we have moved back into a dream, or if this is merely the image of a dream become reality. It is reminiscent of In Another Country, wherein Hong leaves seemingly throwaway moments that reappear and establish a sort of continuity between three completely separate stories.

Another example is that initial conversation at the shop, where the man tells Haewon and her mother that they can pay whatever they want to for the books outside. Haewon is reluctant, because she claims that how much she pays will show who she is. Not only do I enjoy Hong’s use of moments like this to reveal character, but I also like the way he brings the moment back later in the film and puts a different twist on it, asking us to pose structural questions of the film and behavioral questions of ourselves.

Another example is that initial conversation at the shop, where the man tells Haewon and her mother that they can pay whatever they want to for the books outside. Haewon is reluctant, because she claims that how much she pays will show who she is. Not only do I enjoy Hong’s use of moments like this to reveal character, but I also like the way he brings the moment back later in the film and puts a different twist on it, asking us to pose structural questions of the film and behavioral questions of ourselves.

If you enjoy long-take cinema and art house sensibilities, I think Nobody’s Daughter Haewon will prove a gratifying experience for you. Tickets are still available for both showings at the festival. Ultimately, I would recommend some of Hong’s other work as well (particularly In Another Country), but be sure to take a page from Hong’s book and watch them slowly and deliberately.