Review: Wisconsin Film Festival

Review: Wisconsin Film Festival

The Traveler (Mossafer) | Abbas Kiarostami | Iran | 1974 | 73 min

Chazen Museum of Art, Friday, March 31, 1:45pm»

Chazen Museum of Art, Sunday, April 2, 12:00pm»

The Traveler, an early short feature film by Abbas Kiarostami, anticipates many themes that appear in his later work, but also showcases a much looser, kinetic visual style. James Kreul reviews the film as part of our 10-day Wisconsin Film Festival preview.

Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s early feature film The Traveler (1974) provides a lively, spirited introduction to his work. It also reveals a different stage of his career for those familiar with Kiarostami through his later films.

Many of Kiarostami’s later themes are here: childhood discoveries, the role of community, and seemingly small moral choices that have a profound emotional impact. While Kiarostami already experiments with the mix of documentary and fiction, use of non-professional actors, and extended takes in The Traveler, its visual style might surprise fans of his later films. Instead of the later austere, meticulously composed static frames, we see haphazard camerawork and editing that gives The Traveler a vibrant, youthful energy.

As I mentioned in the Big Auteurs preview, Kiarostami’s death last July hit me hard. The rise in Western critical attention to Iranian cinema in the 1990s corresponded with my opportunity to discover Iranian cinema at the UW-Cinematheque and the Wisconsin Film Festival. When Kiarostami solidified the global status of Iranian cinema with his Palm d’Or victory for Taste of Cherry in 1997, many people felt that it was a belated acknowledgement of his so-called “Koker trilogy”: Where is the Friend’s Home? (1987), And Life Goes On (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994). The trilogy, taken as a whole, mixes narrative simplicity with structural and intertextual audacity in a way that remains thrilling.

Critics and scholars hailed Iran as one of the most important national cinemas by the time I caught up with Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy, along with the films of Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Majid Majidi, and Jafar Panahi. But Kiarostami had already been making films for over 20 years at that point, initially through his work at the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. As he ventured into personal filmmaking, children remained central to many of his early films from The Bread and Alley (1970) through Homework (1989). Only relatively recently have Western critics and scholars sought to examine the relationship between Kiarostami’s early and late work.

In The Traveler, 12-year-old Qassem (played by the charismatic Ghāsem Jolā’i) lives in the small city of Malayer in northwest Iran. Qassem cares about nothing but soccer. He skips classes to practice with his makeshift soccer team. He devises an alibi for missing school by faking a toothache. He surreptitiously reads a soccer magazine during his lessons. And he misbehaves at home: his mother arrives at the school to ask the schoolmaster to punish Qassem for stealing money. But somehow, Qassem remains a sympathetic protagonist, because he loves soccer so purely. He designs an elaborate plot to see his favorite soccer player play miles away in Tehran, and we want him to succeed.

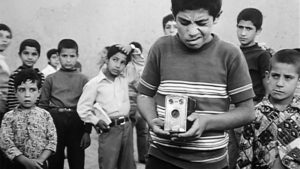

A broken camera provides a key to his plot. He first tries to pawn it for bus ticket money. When that fails, he conceives a scam to raise more money by pretending to take pictures of his classmates, who pay him in advance for the portraits. His door-to-door efforts to raise money anticipates the door-to-door search for the young boy’s friend in Where is the Friend’s Home, and the montage of faces posing in front of Qassem’s broken camera provides a condensed version of the talking head interviews with children in Homework.

The staged action seems to take place within unstaged environments, and the visual style features loose, handheld camerawork and quick cuts. The opening street soccer match between Qassem’s friends and a rival team seems more like a direct cinema documentary than Kiarostami’s later signature style.

The Traveler also connects with Kiarostami’s other work through its emotional impact. Small decisions Qassem makes end up having big consequences, and we alternate between wanting him to succeed and worrying that he will get his comeuppance for his misdeeds. Qassem displays a mix of innocence and street savvy as he makes his way through his adventure. He always has an answer, or a change in tactics, when he faces an obstacle. But he’s also unwilling to admit when he’s acting beyond his experience. Keeping the drama simple and direct, Kiarostami often triggers emotional responses by borrowing from the neo-realism playbook (especially with music cues). But even neo-realism doesn’t prepare you for the complexity of your emotional response.

I also mentioned in the Big Auteurs preview that the final shot in Through the Olive Trees remains one of my favorites of all time. That shot somehow delivers a tremendous emotional punch despite being very far from the dramatic action. The last camera position in The Traveler is similarly far from Qassem as he realizes his situation. The final shot in The Traveler is not as transcendent as Through the Olive Trees, but it quietly jabs you before cutting to black.

The relative simplicity and broad appeal of The Traveler makes it a strong Wisconsin Film Festival ticket even if you’ve never seen a Kiarostami film. But the early display of themes and techniques that will blossom later in his work also makes it a priority for Kiarostami fans. And both sets of film fans will appreciate the opportunity to see Kiarostami’s last completed film, the short, Take Me Home, at the Festival screenings.