Welles Week: Part Four of Five

Welles Week: Part Four of Five

Citizen Kane | Orson Welles | USA | 1941 | 119 minutes

UW Cinematheque, 4070 Vilas Hall, Saturday January 24, 7:00pm»

James Kreul gives you five good reasons to re-visit Citizen Kane—in five shots.

For the fourth installment of our Welles Week leading up to the start of Orson Welles: A Centennial Celebration at the UW Cinematheque, I decided to take fresh look at the opening night film, Citizen Kane (1941). Maybe you’ve heard of it. Welles’s debut feature is one of the most acclaimed films ever made, and it only recently ended its 50-year tenure at the top of the Sight and Sound critics poll for the “Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time” (it now ranks at #2, behind Hitchcock’s Vertigo). Because of its accolades, one might think that everything has already been said about it. If you’ve seen it before, you might think that there’s no reason to see it again. But over the years I have found that the film greatly benefits from repeat viewings. Despite leading numerous discussion sections, grading pages of student essays, reading scholarly and popular articles, and just re-visiting the film on my own from time to time, I can honestly say that I continue to learn something each time I watch Citizen Kane.

Spoiler Alert: Read no further if you have not seen Citizen Kane.

You’ve had 74 years to see it at this point. You’ll probably find more spoilers in the popular culture at large than you will find in this entry (we’ve all seen the Peanuts cartoon where Lucy explains “Rosebud” to Linus while he’s watching Kane, and that’s over 40 years old). My intention here is not to introduce but to re-introduce you to Citizen Kane. There are many great moments in the film to watch and re-watch, but here I will discuss shots and sequences that have changed for me over the years due to particular screenings or experiences with the film.

I will focus on five shots. Of course, in the age of YouTube I could just rip and post the shots here and let you enjoy them until they are taken down for copyright violations (though I would have a solid fair use argument). But there’s something to be said for taking some time to savor these images in static form to help us understand why they become vibrant when in motion.

1. News on the March screening room (14:35)

I could have selected any frame from the projection room scene because the whole sequence is a master’s class in black-and-white cinematography. This scene has changed the most for me since first seeing the film on VHS in Bill Keyes’s Film Study class at West High School in the mid-1980s. I eventually saw the film in 16mm in college, which was a significantly improved experience. But wow, there’s nothing quite like seeing these images in a good 35mm print (like Saturday’s Cinematheque screening). My first impressions in high school viewings were about how effectively the faces were hidden in shadow. But after seeing good 35mm prints, I became fascinated by how much detail you can see the faces in the projection room. One sometimes forgets that what makes black-and-white cinematography beautiful is a well utilized range of greys. While our eyes might first notice how Mr. Rawlston’s (Phillip Van Zandt, screen right) silhouette goes near black, let your eyes wander over to the range of greys on Jerry Thompson (William Alland, screen left). Not just on his jacket, look at the subtle differences from his cheek to his eyes to his forehead as they catch the light reflected off of the desk. You can’t see this sequence too many times. Every time it is a completely dazzling spectacle of light and dark.

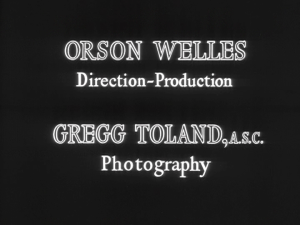

Despite Welles’s audacious ambition and achievement with Citizen Kane, there’s good reason he insisted on sharing his closing credit with cinematographer Gregg Toland. Just take a look at Hearts of Age or Too Much Johnson (see Monday’s Welles Week entry) and you’ll realize that Welles always had the imagination, but initially didn’t have the craftsmanship. Many of his later European films, despite having his signature visual style, often don’t have the same technical polish (sometimes hindering them, sometimes adding to their charm, as noted by Jake Smith and Jay Antani this week). Watching Kane often prompts many “What if?” questions, including “What if Welles had a chance to work with Toland again?”

Despite Welles’s audacious ambition and achievement with Citizen Kane, there’s good reason he insisted on sharing his closing credit with cinematographer Gregg Toland. Just take a look at Hearts of Age or Too Much Johnson (see Monday’s Welles Week entry) and you’ll realize that Welles always had the imagination, but initially didn’t have the craftsmanship. Many of his later European films, despite having his signature visual style, often don’t have the same technical polish (sometimes hindering them, sometimes adding to their charm, as noted by Jake Smith and Jay Antani this week). Watching Kane often prompts many “What if?” questions, including “What if Welles had a chance to work with Toland again?”

2. Mrs. Kane introduces Charlie to Mr. Thatcher (21:14 – 23:44)

Speaking of “What ifs,” what if Welles had worked more frequently with Agnes Moorehead, who delivers one of the most devastating lines in the history of cinema in her role as Mary Kane: “I’ve got his trunk all packed…I’ve had it packed for a week now.” Moorehead only worked with Welles once more, just as memorably, as Aunt Fanny in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), and most of us know her as Endora on television’s Bewitched. The whole scene at Mrs. Kane’s Boarding House is a tour-de-force of performance, staging and camera movement in in the service of storytelling. Another option here would be to dissect the shot previous to this one, which looks out the window at young Charles as he plays, because it inaugurates an important window motif throughout the film. But I’ll discuss this equally impressive and significant shot, because it is a microcosm of the film’s central conflicts and themes. It begins as Mary opens the window that her husband Jim has just closed, so that she can hear Charles play and call to him from the window. Mr. Thatcher notes that it is getting late and suggests that it might be time for him to meet the boy, and Mary answers with the line quoted above.

(In an example of great minds thinking alike, as I completed this analysis Wednesday night I discovered that Evan Davis had chosen to discuss these same moments in his discussion of Agnes Moorehead for the UW Cinematheque blog. Davis observes, “Those two shots never fail to bring me to tears, and it’s all because of Agnes Moorehead’s quietly devastating performance.”)

Mrs. Kane crosses screen left and Mr. Thatcher and Mr. Kane follow her to the door. The camera, positioned outside of the window, tracks back and to the left until Charles and his snowman are in the middle ground. Mrs. Kane and Thatcher exit the Boarding House to approach Charles and position themselves in the foreground screen left. Charles joins them on screen right as Mr. Kane approaches but holds back in the middle of the background. What follows must be watched multiple times to pick up on all of the beat changes based on the text and subtext. Each viewing can be different depending on which character you decide to focus your attention. Each of the adults pretend that the situation is different than it really is for their own sake or for Charles’s sake. Mr. Kane wants to give the impression that he is a loving father and is still in control of the family. Mr. Thatcher wants to impress upon Charles that leaving his family will be a grand, exciting adventure, even though he only acts in the interest of the bank. Mrs. Kane wants to protect Charles from Mr. Kane, even if that means losing him by handing him over to Mr. Thatcher. Each beat change is marked with subtle shifts in staging and positioning within the frame.

Mrs. Kane crosses screen left and Mr. Thatcher and Mr. Kane follow her to the door. The camera, positioned outside of the window, tracks back and to the left until Charles and his snowman are in the middle ground. Mrs. Kane and Thatcher exit the Boarding House to approach Charles and position themselves in the foreground screen left. Charles joins them on screen right as Mr. Kane approaches but holds back in the middle of the background. What follows must be watched multiple times to pick up on all of the beat changes based on the text and subtext. Each viewing can be different depending on which character you decide to focus your attention. Each of the adults pretend that the situation is different than it really is for their own sake or for Charles’s sake. Mr. Kane wants to give the impression that he is a loving father and is still in control of the family. Mr. Thatcher wants to impress upon Charles that leaving his family will be a grand, exciting adventure, even though he only acts in the interest of the bank. Mrs. Kane wants to protect Charles from Mr. Kane, even if that means losing him by handing him over to Mr. Thatcher. Each beat change is marked with subtle shifts in staging and positioning within the frame.

Mr. Kane begins to speak to Charles, and Charles pivots to join him in the background until he is called by his mother, who crosses to the right side of the screen. Charles returns to the foreground between Mr. Thatcher and Mrs. Kane, and looks up to his mother. Mrs. Kane explains to Charles that he will leave on the morning train, and Charles asks her if she is going too. When Mr. Thatcher interrupts to answer Charles’s question, Charles pivots and glares at Mr. Thatcher, who pauses. That pivot and glare is the start of a conflict that will shape the rest of Charles Foster Kane’s life.

Mr. Kane begins to speak to Charles, and Charles pivots to join him in the background until he is called by his mother, who crosses to the right side of the screen. Charles returns to the foreground between Mr. Thatcher and Mrs. Kane, and looks up to his mother. Mrs. Kane explains to Charles that he will leave on the morning train, and Charles asks her if she is going too. When Mr. Thatcher interrupts to answer Charles’s question, Charles pivots and glares at Mr. Thatcher, who pauses. That pivot and glare is the start of a conflict that will shape the rest of Charles Foster Kane’s life.

Mr. Kane asserts himself again and joins the group in the foreground, positioning himself on screen left with Mr. Thatcher. Both men attempt to persuade Charles that leaving his mother will be a great adventure, but division between the two sides of the screen tells another story. Mr. Kane gets bolder and moves closer to Charles, so Mrs. Kane again shifts her position and places herself between Mr. Kane and Charles, placing her hands on Charles’s shoulders. Mr. Thatcher attempts to extend his hand to Charles, but Charles resists him by holding up his sled between them.

Mr. Kane asserts himself again and joins the group in the foreground, positioning himself on screen left with Mr. Thatcher. Both men attempt to persuade Charles that leaving his mother will be a great adventure, but division between the two sides of the screen tells another story. Mr. Kane gets bolder and moves closer to Charles, so Mrs. Kane again shifts her position and places herself between Mr. Kane and Charles, placing her hands on Charles’s shoulders. Mr. Thatcher attempts to extend his hand to Charles, but Charles resists him by holding up his sled between them.  When Mr. Thatcher attempts again, Charles pushes him back with the sled, and the camera pans left to follow Mr. and Mrs. Kane as they attempt to stop Charlie’s attack on Mr. Thatcher. As Mr. Kane helps Mr. Thatcher up off of the ground, Charles runs by them and Mr. Kane attempts to hit Charles. Mrs. Kane stops Mr. Kane by yelling, “Jim!” and again places herself between Charles and Mr. Kane. Mr. Kane apologizes to Mr. Thatcher and suggests that what Charles needs is “a good thrashing.”

When Mr. Thatcher attempts again, Charles pushes him back with the sled, and the camera pans left to follow Mr. and Mrs. Kane as they attempt to stop Charlie’s attack on Mr. Thatcher. As Mr. Kane helps Mr. Thatcher up off of the ground, Charles runs by them and Mr. Kane attempts to hit Charles. Mrs. Kane stops Mr. Kane by yelling, “Jim!” and again places herself between Charles and Mr. Kane. Mr. Kane apologizes to Mr. Thatcher and suggests that what Charles needs is “a good thrashing.”

“That’s what you think, is it Jim?” Mrs. Kane asks as the group repositions itself: Mr. Kane and Mr. Thatcher on screen left tower above a hunched Mrs. Kane, who positions herself over Charlie and holds him in her arms on screen right. The camera quickly tracks in to the group to punctuate Mrs. Kane’s question and Mr. Kane’s answer, “Yes!” The shot ends with her response providing a sound bridge to the next shot, a close-up of Mrs. Kane that tilts down to a close-up of Charles: “That’s why he’s going to be brought up where you can’t get at him.”

That’s just one shot, people. It’s a complete 2.5 minute film in itself. There’s still another 95 minutes left in the film, filled with similarly complicated and rewarding shots. They just don’t make ’em like this anymore.

3. Charles Foster Kane offers to make Susan Alexander laugh (57:15)

Shot #3 provides an example of how I missed an important detail despite many viewings, and it illustrates how well designed the film is overall. A student finally pointed out to me a few years ago that in terms of story time, this is the first appearance of the snow globe that years later Kane would drop after uttering his final word, “Rosebud.”

“Plot” is the order in which we see events presented by the filmmaker, and “story” is the chronological series of events that we construct in our heads based upon information presented in the plot. The first appearance of the snow globe in the plot is at the beginning of the film when Kane dies. But my Shot #4 is the earliest story event in which the snow globe appears, shortly after Kane first meets Susan and they go to her apartment so that he can clean off the mud that had been splashed on him in the street. Now that we realize that the snow globe has been with Susan from her first appearance in the story, it makes more sense for it to be in her room in Xanadu as Kane rampages after she leaves him. It also makes more sense that Kane associates the globe with “Rosebud,” not only because of the snow but also because of the connections between Kane’s meeting Susan and Kane’s memories of his mother. Before Kane was splashed with the mud, he had just visited the storage space where his mother’s belongings had been shipped. Kane discusses this with Susan shortly after Shot #3.

I’ll let Dr. Freud explain other reasons for Kane’s associations between Susan and his mother. My point here is that Citizen Kane is an intricately designed film and the simple placement of the snow globe on the dressing table here is one of many significant details that can be discovered after multiple viewings (though I have to admit that my student noticed it in her first viewing).

4. Kane discovers his “Declaration of Principles” in envelope from Leland (1:32:53)

Kane’s discovery of his Declaration of Principles in Leland’s envelope reminds us of another reason to watch the film again: it is a great story, told with an imaginative and innovative screenplay. (Kane‘s sole Academy Award was for Best Original Screenplay for Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz.) Once you know the story, many pleasures derive from watching Kane again with first-timers. Shot #4 significantly changed for me when I saw it outside of an academic context with a general audience. As great as classroom screenings can be, sometimes they can play flat because the students feel obligated to be there, which is different than going out to the theater to see a movie. During the 50th anniversary re-release of Citizen Kane I had a chance to see the film at the Majestic Theater, which was the most fun I had at a theater that year.

At the Majestic screening, when Kane pulls out the Declaration of Principles there were several audible gasps throughout the audience. Having assumed that everyone there had seen the film already, I was completely shocked by the audience being shocked, and it was exhilarating for all of us. First-timers didn’t see it coming, and they experienced it for what it truly is if you’re engaged with the story: a total burn. This wasn’t an academic analysis of the film, this was a from-the-gut reaction from moviegoers with popcorn tubs in their laps, hanging on each twist and reveal with full engagement. We must not forget that in addition to being a great work of cinematic art, Citizen Kane is a thoroughly entertaining and emotionally affecting film. In fact Kane might be the ultimate example of why we should abandon the false dichotomy between art and entertainment.

To return for a moment to the analytical part of my brain: As I assembled these shots I discovered another example of Kane‘s intricate visual design. Compare and contrast the staging and framing in Shots #3 and #4. Of course I knew that there was a motif involving Kane towering over Susan, which culminates in the scene where he slaps her after she mocks him. I had thought about how the slap scene echoed Susan’s defiance in the Declaration of Principles scene, but I had not considered how Kane’s towering over her was in play even in their first story scene together. So there you go. Another discovery (for me, anyway).

5. “Like the time his wife left him…” (1:47:12)

This is a great moment in the film because it foregrounds the visceral experience of the cinema. Everyone remembers this shot as the “WTF?” moment in their first viewing. On subsequent viewings, you either forget that it’s coming up so you’re startled again; or you remember exactly where it is coming up so you can savor the moment as people around you are startled. This moment in the film plays differently at almost every screening, because no one knows what to do with it. Often the shock is followed by awkward, embarrassed chuckles. It’s might be the best example of Welles truly playing with the medium just to mess with us a bit.

I’ll end with this shot because it rounds out the four areas of film style in these examples. Most of my examples focused on cinematography and mise-en-scene, but this example plays with both sound and editing to provide a genuine “shock cut.” It is one of the most memorable and creative uses of sound in the film, ranking with Kane’s clapping at the end of Susan’s debut and the recording of Susan’s singing winding down just before her suicide attempt is discovered. Welles and company truly were running on all cylinders in all departments, and I could go on to explain how almost every shot and scene in Citizen Kane can teach us something about cinematography, mise-en-scene, sound, editing, screenwriting, performance, and, oh yeah, life. But I’d rather hear back from readers after Saturday’s screening of Citizen Kane at the UW Cinematheque with other examples of memorable or favorite moments from the film. Please feel free to share yours in the comments below.